30 minutes with Carlo Crivelli

01 - Room XXII

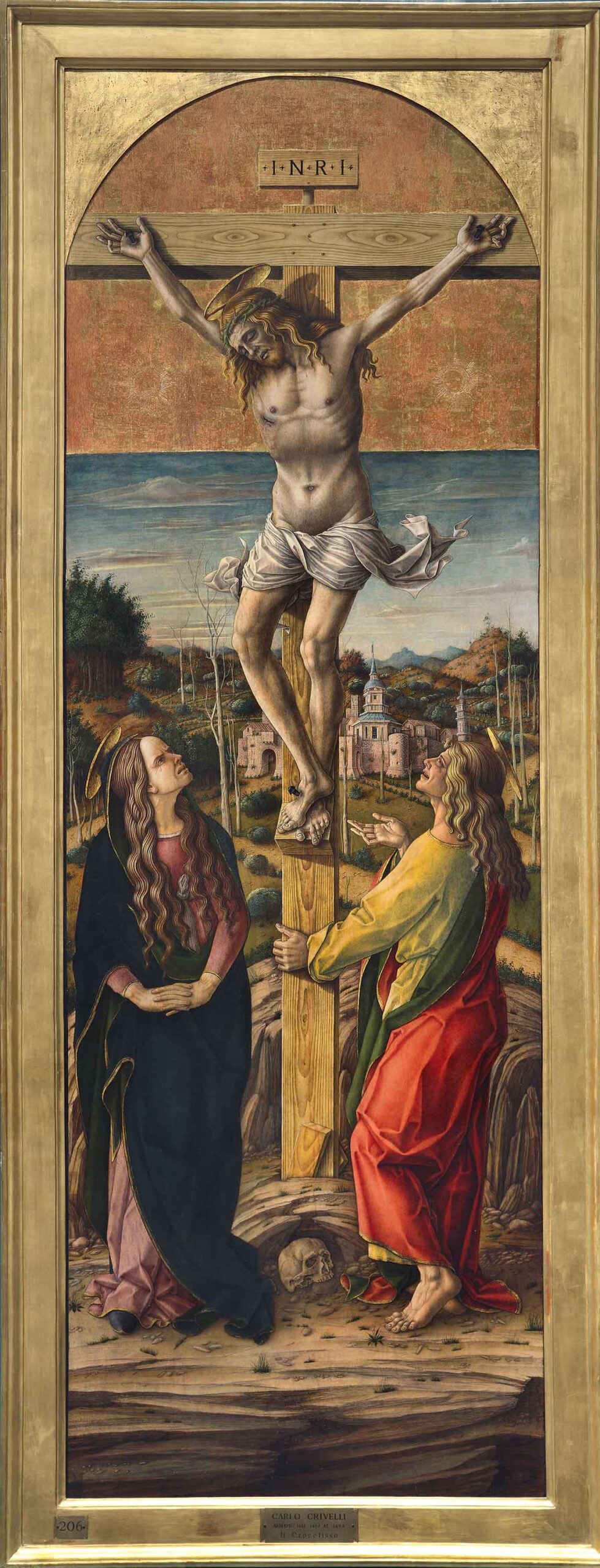

You are now in room XXII, truly a ‘golden chamber’, containing masterworks from the Marche region; most of the works here are polyptychs, huge complex mechanisms made up of various parts, which were used to decorate the altars in churches all over Italy between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. They were composed of a group of images held together by elaborate cornices, intricately decorated with cymatium molding, spires, columns, and reliefs. During Napoleon’s dominion at the beginning of the 1800’s, these polyptychs were stolen from the temples in which they were set up, taken apart and resold separately to collectors and antique shops; some of the exhibited works are even lacking cornices and those that you can see were rebuilt in the mid-1800s by artisans who recreated works or sections of works ‘in style` so that they could finally assume an appearance resembling the original. Gold is the undisputed protagonist of this room: cornices are golden, the backgrounds in the paintings themselves takes on golden hues, and the dense sheared decorations portraying complicated ornamental motifs behind the figures are also golden.

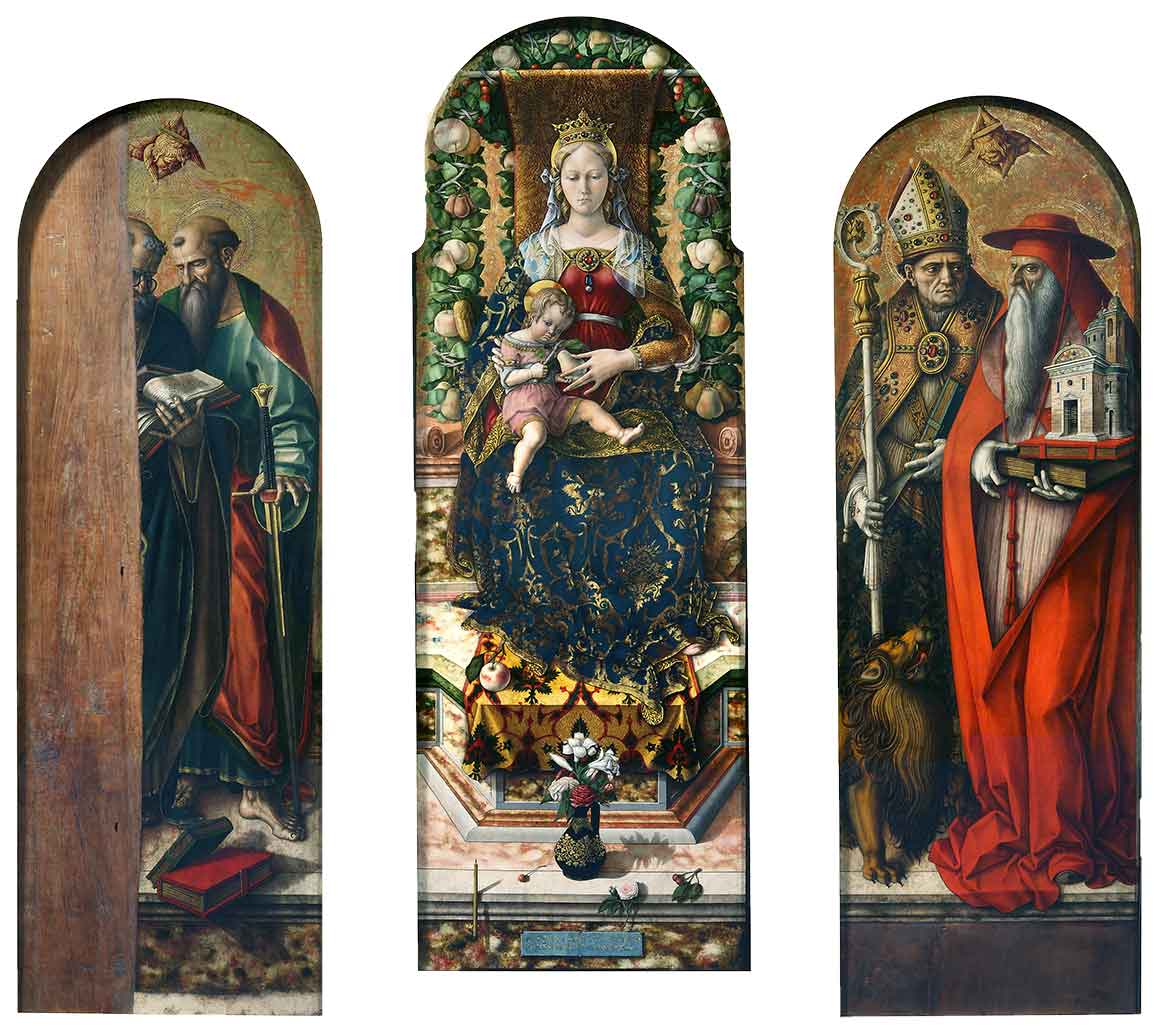

The wall you find before you, as you enter room XXI, is dedicated to Carlo Crivelli. On the right, the Madonna della Candeletta, and on the left, the Triptych of Camerino.

02 - Interpretation of the work

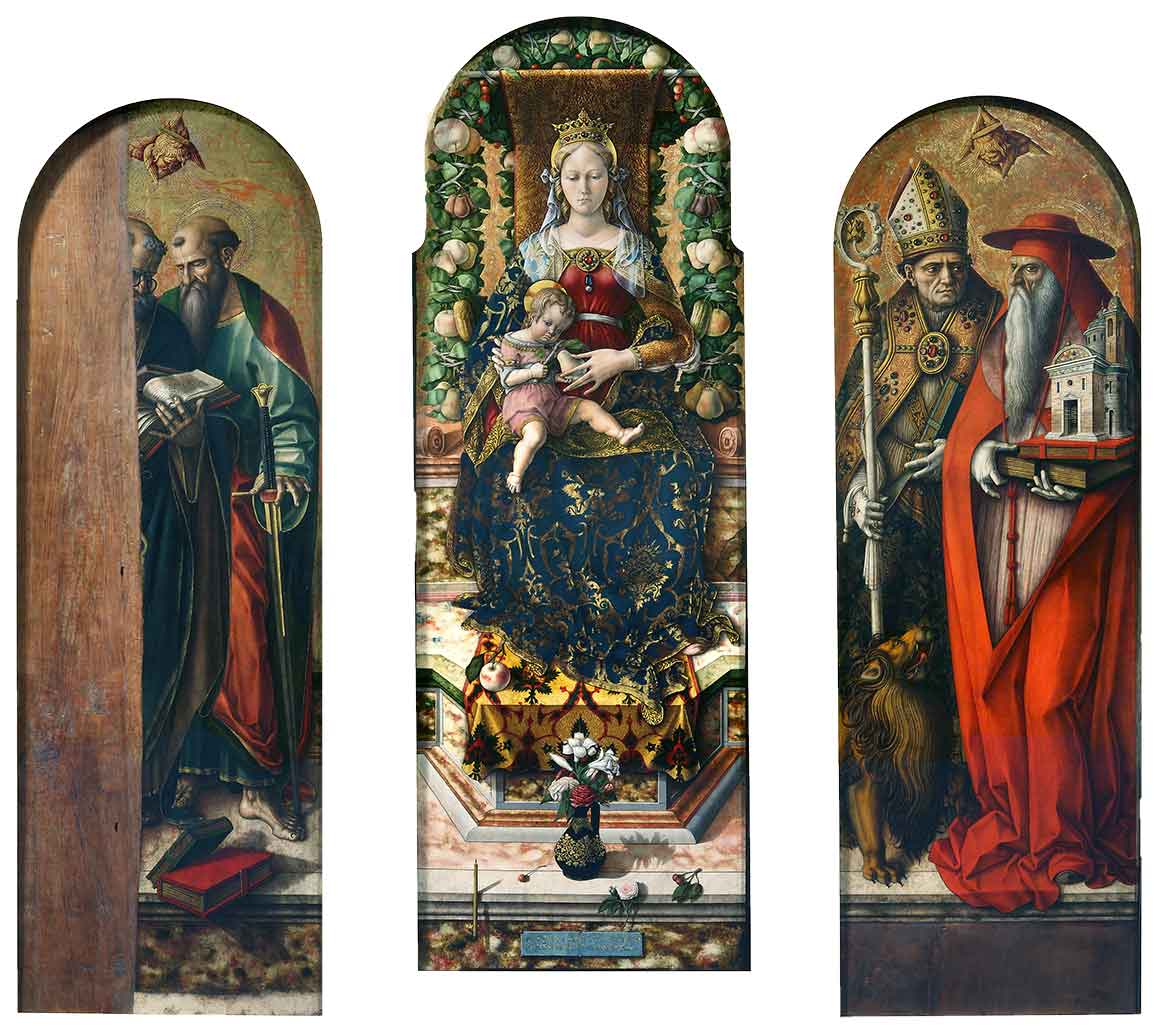

The central compartment of the polyptych depicts Virgin Mary sitting on a throne magnificently garnished with a precious red drape. She is wrapped in a similarly luxurious green and gold mantle, the folds of which fall softly to her feet. The Child sits on her left knee, and is clad in a simple white vest. In His hands He is holding a small bird (maybe a goldfinch, symbol of the Passion); His face is endearingly sulky and lost in thought. Mary’s slender hands hold him in a gesture of care and sweetness in which she nonetheless maintains the composure of a queen.

On the sides, four figures fill the space allotted by the painter: to the left Saint Peter, grim and strict, and at his side St. Dominic, whose expression is alight with mystic contemplation, just as Saint Peter Martyr’s is on the right. Beside the latter (Saint Peter Martyr) you can see the young Saint Venanzio, patron of Camerino, as he offers Virgin Mary a miniature model of the city: impeccably dressed, in red tights and blazing red beret, he contemplates her, motionless.

Gold is the other hero of the triptych: we see it shine, dazzling with its solid presence, in St. Peter’s tiara, in the mantle clasp, in the cross crowning the pastoral staff, in the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven which, with their three-dimensionality, seem to reach out into our universe, the universe of beholders. But above all gold is in the background from which the figures stand out: a golden tapestry with extremely refined perforations which decorate the work with an arcaic, medieval look.

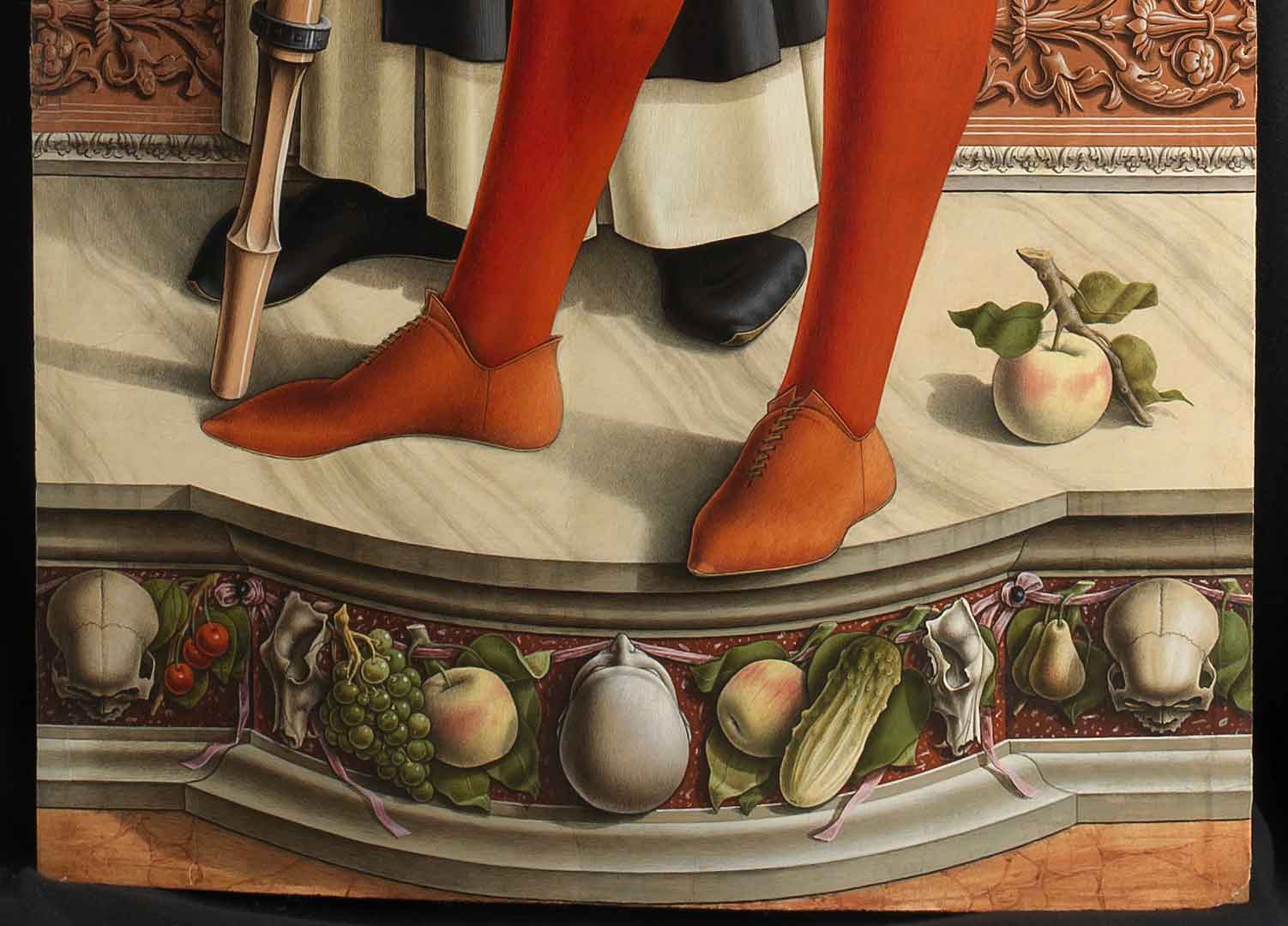

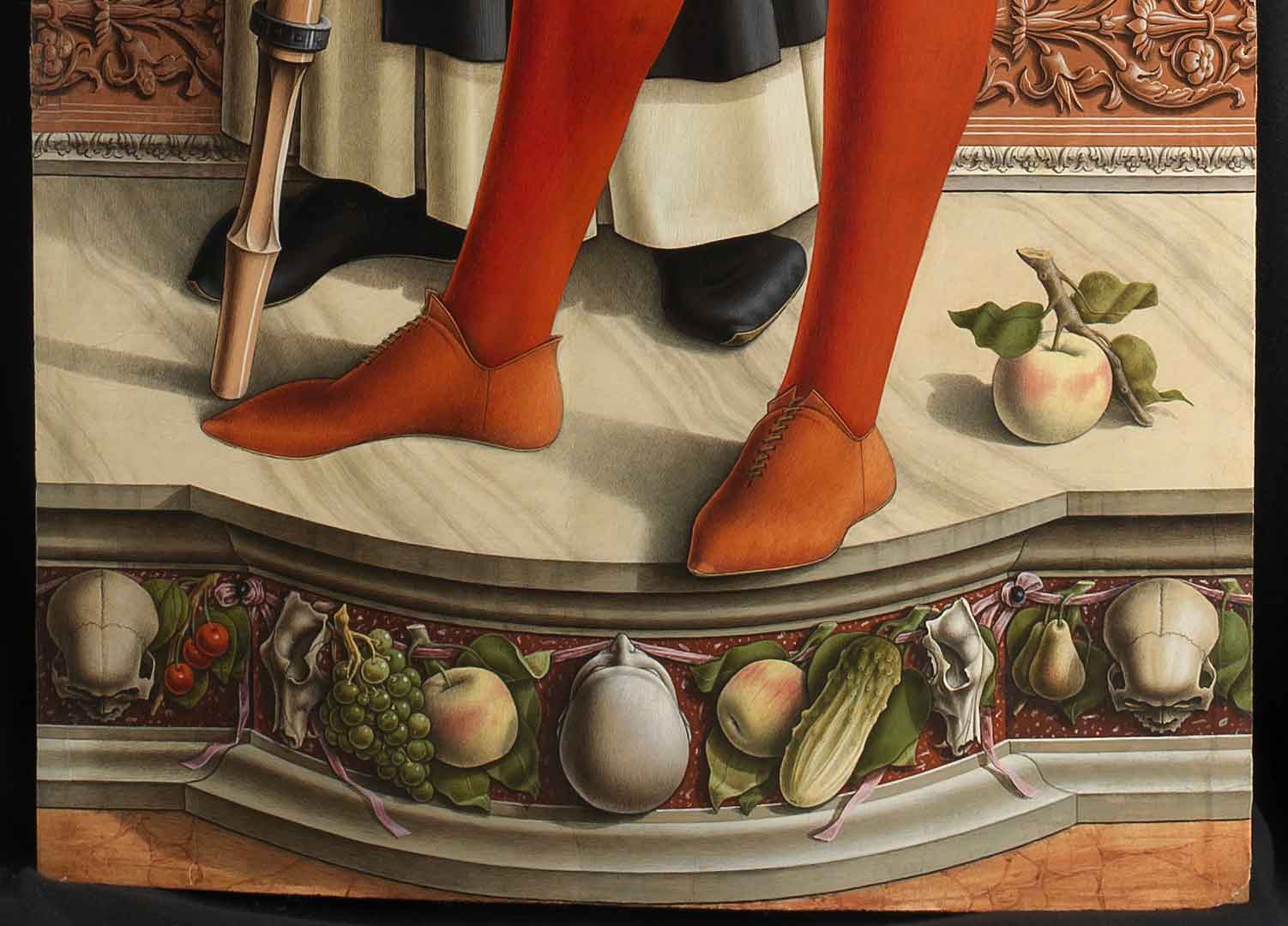

Yet when we take a close look, none of the characters is shadowed by all that gold, because the artist defined -with rigorous prospectic precision- the space each of them would occupy. With the firm and accurate strokes of his drawing, he positions the figures in a way that, after some observation, turns out to be tremendously effective. The figures are standing on a marble base which runs the length of the triptych and confers prospective and compositional unity to the painting itself; its decorations include marble reliefs spaced out by vegetable representations, among which a cucumber, which comes up quite often in Crivelli’s works. It’s believed the cucumber might symbolize the Resurrection, since tradition narrates that Jonah, having emerged alive after three days inside the whale, reached firm land beside a cucumber plant; according to others, this vegetable represents original sin, in contrast to Virgin Mary’s purity.

Another important element in this work is the variety of precious cloths depicted, with a quality and an effectiveness which, still today, leave spectators in awe: the red drape of honor behind the Madonna’s back – a Damask – which highlights her at the center of the composition; the regal mantle in green and gold; the colorful garments worn by the young Venanzio and the beret in red velvet, cleverly rendered thanks to the use of lacquer in a patina technique. It all points to the artist’s meticulous attention to the great number of precious cloths produced by a true ‘luxury industry’ which had with passing time taken this luxury to a truly breathtaking level; so it was attention not so much to the past as to the historical process itself and to the contemporary societies in which the creation of precious textile material was not only destined to adorn noblewomen and regal palaces, but also churches, holy images and objects used for worship.

Underneath the side compartments, you can see two surviving predellas, which arrived to Milan in the same box but were only attributed to the polyptych at the beginning of the twentieth century: they depict St. Anthony Abbot, St. Jerome, and St. Andrew on the left; St. James, St. Bernardine of Siena and Blessed Ugolino Magalotti from Fiegni on the right, each with attributes that characterize them.

03 - Iconography

The four saints in the triptych present traditional iconography and attributes which allow for them to be identified: St. Peter is wearing the tiara and the luxurious mantle or cope. A cope is a wide liturgical vest with a semi-circular shape, open at the front, and closed on the chest with a precious clasp. He holds in his left hand the pastoral staff, topped with a cross, and in the right the Holy Book and the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven, one golden, the other silver: they are the most common attribute of this saint both in medieval and modern depictions, and they are a reference to a number of meanings. The first is the power to open or close the doors to God’s Kingdom, and, through the Church, to let in only those who are worthy; the second is linked to the words ‘tie’ and ‘untie’ pronounced by Jesus in the gospel of St. Matthew, and with which He confers Peter the power to condemn or absolve, and therefore to admit or exclude souls from Paradise. The two keys became, in medieval times, the insignia of papal authority in his double nature, divine and worldly.

St. Dominic, more towards the back, is dressed in the traditional outfit of the Order of Preachers, and his attribute is the book he holds in the nook of his left arm, which symbolizes the attention given by the Order to the study of doctrine as a weapon against heresy. Two lilies peek out from within the book’s pages, evoking the ideal of chastity, as well as distinguishing the saint from Saint Thomas Aquinas who is also generally represented holding a book.

To the right another Dominican, Saint Peter Martyr, represented with a pruning hook cleaving his head and a dagger stuck in his chest; both recall the way in which he was martirized at the hands of goons in 1252 in Barlassina, as he was heading with some companions from Como to Milan to fight the heretics. Beside him young Venanzio, sumptuously dressed in the style of that time, courteously offers Virgin Mary the small model of the city he protects, which is Camerino. This saint was a 15-year-old boy belonging to a noble family of the city’s senatorial class; once converted to Christianity, he underwent an excrutiating persecution on the part of Roman authorities, and was tortured until his beheading in 253, with another ten Christians. His body still rests in the basilica which was dedicated to him, outside the walls of Camerino.

In the center, the Virgin sitting on a throne, holding the Child in a regal but affectionate stance, recalls the sacred characters commonly depicted in Italian paintings of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, a time in which the function of sacred images changed radically as a result of the appearance of mendicant orders. Fresh representations began to be preferred around that time, less and less tied to the elevated language of theologists, and closer to a secular public, which was growing fast. Sacred and holy characters began taking on more human traits, intending to make the faithful better understand the centrality of Christ’s incarnation in God’s salvation plan through a process of empathy.

04 - Technique

Crivelli’s eye-catching panels, masterfully harmonized and brought to life by the painter’s skill, reveal to us the presence of a preparatory design which was paramount in organizing the composition of the work. Even if it still hasn’t been possible to grasp the exact procedure used in Crivelli’s workshop, and mainly what came before the preparatory design, some discoveries were made thanks to delicate infra-red tests. In this way it came to be known that the painter gave the drawing phase an organizing function within the composition, but used it to define volumes of bodies as well. A very light stroke, made of diagonal parallel lines which Crivelli learned during his experience as an apprentice at Francesco Squarcione’s workshop in Padova.

In addition to this special ‘pictorial design’ technique, we can also find the classical broken line brush stroke, as for example in the frieze at Virgin Mary’s feet. No traces of dusting remain; their presence would have suggested the use of preparatory paper boards to copy certain details, mainly decorations, which tend to fall into a pattern. In complex designs as well, like the architecture involved in the throne, research shows that rather than being a precise graphic projection, what we see is the sum of repeated attempts of the artist to find a plausible composition. The final result is a prospective installation in which projections of elements converge towards the vertical axis of symmetry, so the panels are not limited to a single vanishing point. Other elements which inevitably capture the observer’s eye are the decorations in relief, which are unexpected in a graphic production characterized by bi-dimensionality: all of St. Peter’s attributes , for example, mask a wooden core fixed to the panel with a nail right at its very center. The core was then covered with the usual mixture of plaster and white glue. At that point, the preparatory drawing was traced as well as the carvings that kept it in sight once the red clay was applied and the gilding or silvering began. Another technique used to produce three-dimensional elements, in this case St. Venanzio’s belt and the saints’ aureoles, is to make a mixture of plaster ground with glue and clay and apply it directly on the panel with a brush to outline the reliefs. In the places where the artist used a mixture with a higher concentration of plaster, as in the dagger and St. Peter Martyr’s sword, he obtained a denser, more malleable material, perfect for medium-sized, non-jutting objects of simple design. So we can see that Crivelli made good use of most or all the pictorical and decorative techniques common in Italian workshops from the eighteenth century onwards. These techniques served greatly to enhance the complex altar mechanisms he created for the churches of the Marchigian countryside.

05 - Life of Carlo Crivelli

Carlo Crivelli was born in Venice in the first half of the fifteenth century, and probably received his initial artistic education in the workshop owned by his father, Jacopo. Little is known about the first part of his life up to 1457, at which point, according to the only surviving document, he was sentenced to six months in jail after being found guilty of adultery. Unfortunately we can’t even attempt to trace his life through his work, since the first dated painting is the Massa Fermana Polyptych, from 1468. However it is precisely from his works that we glean that his education had Venetian roots, in a cultural growing pot that included painters like Jacopo Bellini, Antonio de Negroponte, and Antonio Vivarini. To this we can add an apprenticeship in Padova, in Francesco Squarcione’s workshop, during the 1450’s, right before his time in Zara, which took place approximately between 1463 and 1467. His Padovan stay left significant traces in his paintings: the central importance of garland-style motifs, for one, and mainly his repetitive use of broken line brush strokes to outline volumes.

The reasons that led Crivelli to settle down in the Marche region, working in the areas found between Ascoli Piceno, Macerata and Camerino, remain a mystery. All we know is that he remained there probably until what we could consider the end of his artistic production, which was 1493. This date appears in the Coronation of the Virgin, di Fabriano, his last known work. In the Marche region he found an audience that truly appreciated the multifaceted language of his works, the brilliant and simultaneously traditional preciousness of his artifacts, his way of depicting a sacred world that was alive and vibrant in a atmosphere that at times became unreal.

06 - Patrons

His patrons belonged to the merchant and notarile echelons of the cities in which he worked, as well as to mendicant orders. Romano di Cola, who commissioned this polyptych, was probably a merchant who lived close by the church of St. Dominic in Camerino. Surviving records offer proof of a continuous dialogue with the mendicant church, in which he had a chapel of his own; we also know he was a representative of Virgin Mary’s Confraternity, which was linked to the Dominican Order because it promoted devotion to the Holy Rosary. He was known to be a generous benefactor of the convent, asking in return that they celebrate a daily mass for him and his family, before the main altar and his triptych.

It was in this merchant burgeoisie of the Marchigian hinterland villages that Crivelli found his main commissioners and patrons, often as a result of the close ties he had with religious orders and with local aristocratics like the da Varano family, lords of Camerino. His works satisfied this public’s love for precious, complex and sumptuous works of art, rich with awesome details referring to a figurative language filled with late Gothic stylistic elements.

07 - The story of this painting

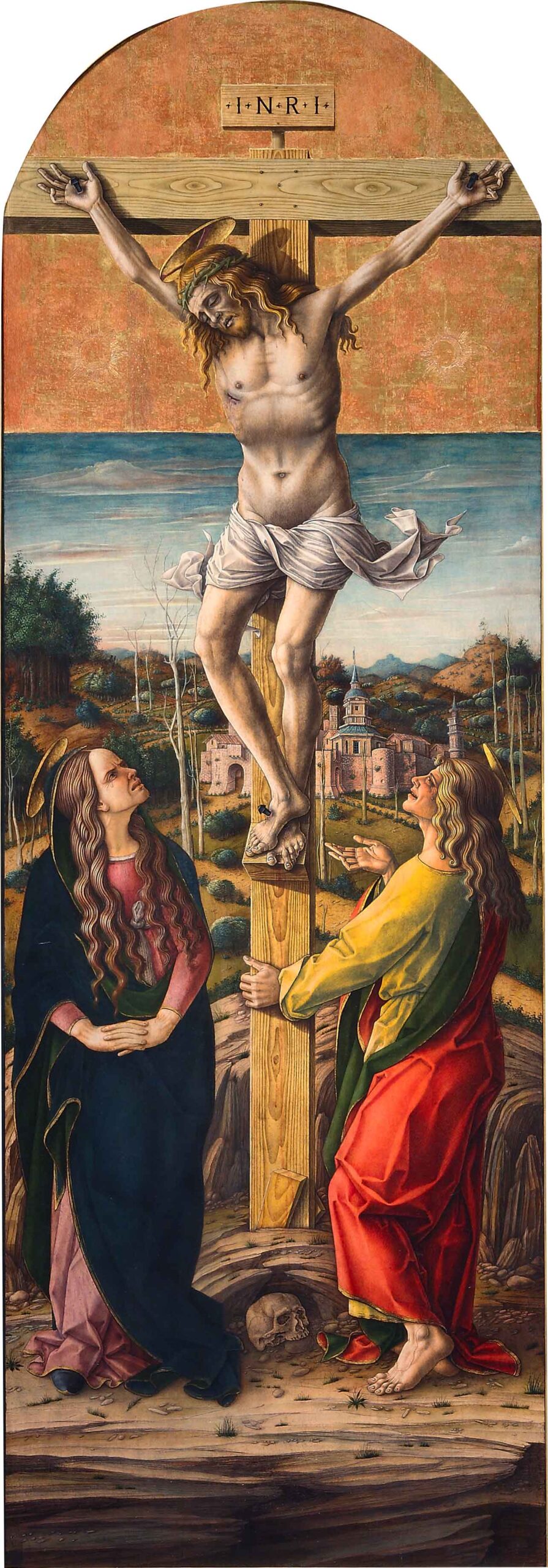

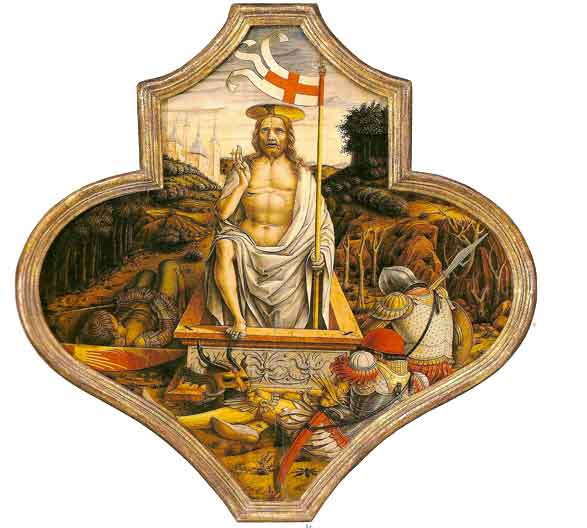

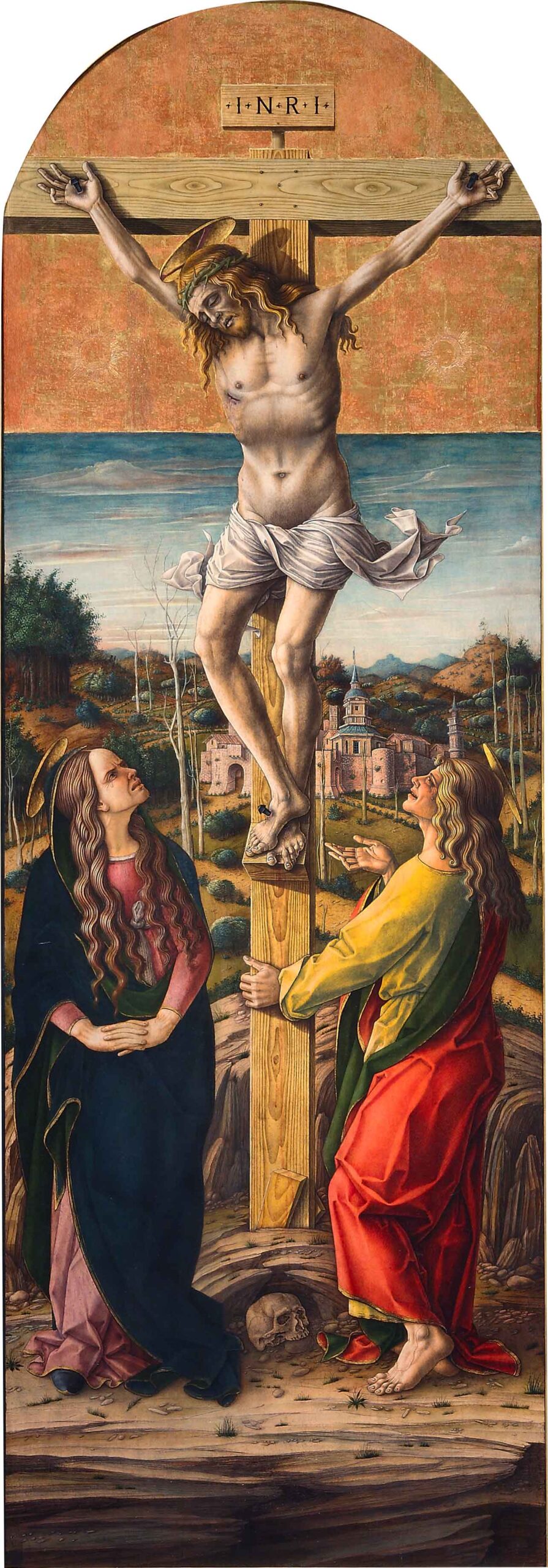

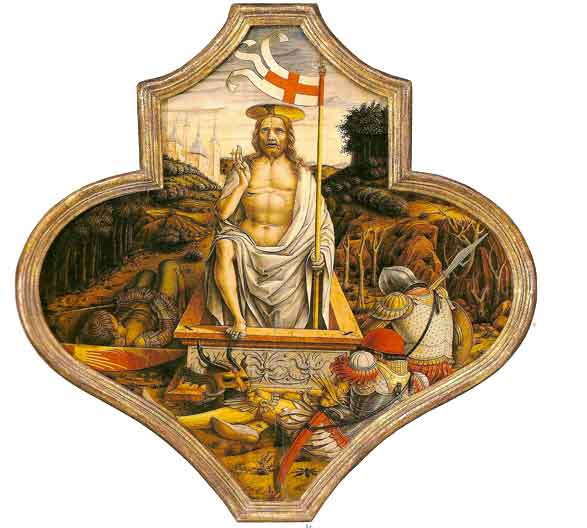

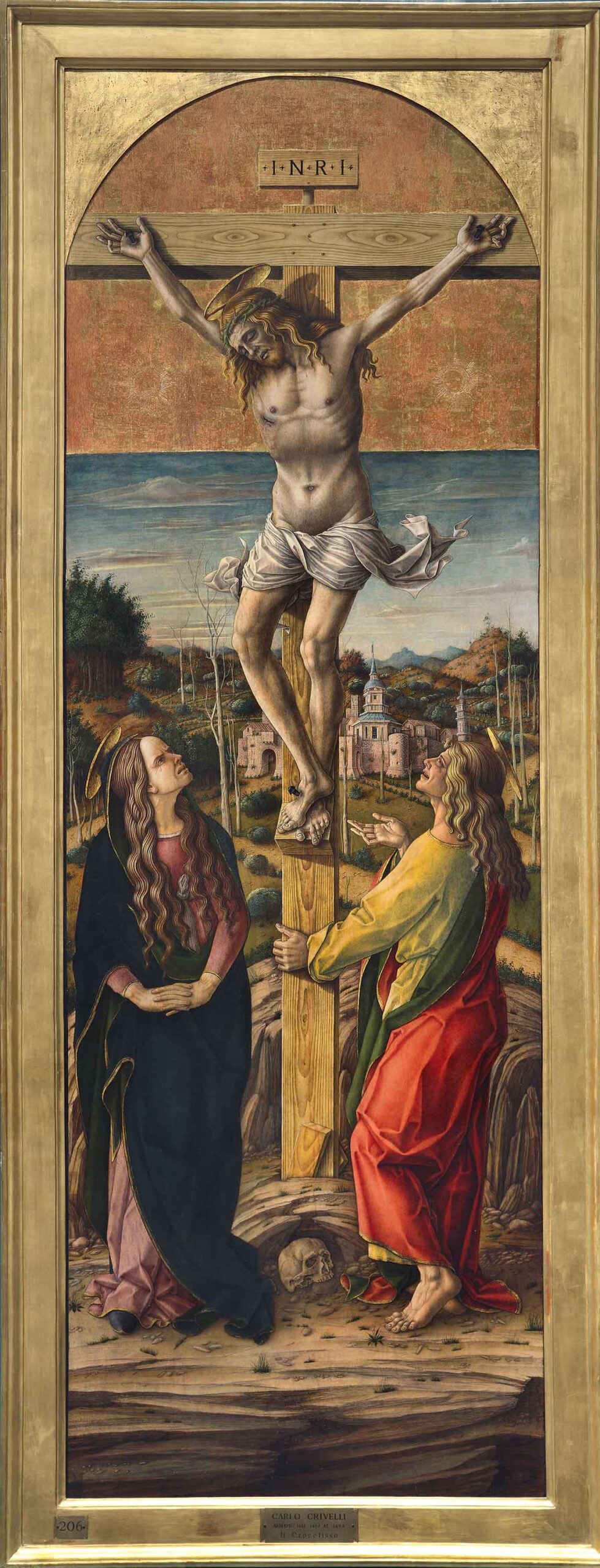

The triptych, originally composed of eight panels and placed at the main altar of the church of St. Dominic in Camerino, arrived in Brera on the 24th of September of 1811 along with other works by the artist. This happened as a result of the requisition of church and convent works in current-day Marche. The boxes contained other works: the Madonna della Candeletta, the Crucifixion, the Delivery of the Keys to St. Peter, and the Annunciation with St. Emidio from Ascoli Piceno. One of the Napoleonic commissaries in charge of requisiting the works of art was Antonio Boccolari; he had taken on the task of choosing what works to send to Milan for a collection meant to teach students about the variety of Italian pictorial schools. It’s fascinating to imagine Boccolari strolling around the church of St. Dominic in Camerino, stopping before the panels of the main altar polyptych. In a closeby room, he then saw the Madonna della Candeletta, which was the Cathedral`s property, and he convinced the canonical clergy to make it available to the government. At last, he had all the works packaged in a box and sent them to Milan. For Crivelli’s paintings, this was but the first of many moves. Boccolari’s spectacular purchase for Brera became a diaspora of sorts. The three cusps of the triptych became the protagonists of one of these exchanges. Depicting a Risen Christ, an Annunciating Angel and an Annunciated Virgin on the sides, they were given away to painter and antiquarian Filippo Benucci. This was the beginning of a long series of negotiations with the curators of the museum, who proposed trading the cusps for small Dutch paintings, still in exhibit today in the rooms dedicated to the art of the Netherlands. The three cusps were put on the antique market and then sold in the mid nineteenth century; today they are split between Frankfurt and Berne.

Fortunately, the three main panels remained in Brera, but still, their stay at the museum was not a peaceful one! In 1824, they suffered heavy restorations which compromised the work’s overall readability. These restorations responded to a highly interpretative conception of what restoration is, and spoiled the appearance of the polyptych. Its original form was that of a complex decorating mechanism, with rather narrow and tapering shapes, with spaces completely filled by the figures and inserted in an ornate wooden cornice of late Gothic style. This original form was taken apart in 1824 and some variations were carried out.. The places where the panel was nailed were punched and gilded like the original backgrounds, creating semi-circular canted compartments. The gilding spread over the whole painting and some figurative parts were amplified. A new gilded box cornice, with spiral columns replaced the original one, making the polyptych merge better with the fifteenth century works of the Venetian region that shared the museum space. In this way, the polyptych lost its peculiar characteristics. The narrow space saturated with things and people, the various prospective indications. The magic of Crivelli’s painting and his strong personality as an artist were ‘flattened’, made to fit a critical vision which placed him at the side of other artists matching his age like Carpaccio, Mantegna and Bellini. During the first half of the twentieth century, Crivelli’s luch with critics seems to falter: his works remain an important part of Brera’s exhibit, but are still right next to the Venetian and Veneto schools to which it allegedly belongs. Few scholars showed a real interest in that painting which was so brightly colored, sumptuous and archaizing. In 1950, the nineteenth-century style cornice was dismounted so that the triptych could be placed in an anonymous pas-partout museum compartment.

It was only around 1990 that Crivelli’s works found the right placement within the room dedicated to Marchigian polyptychs, and in which still today we can admire the triptych of St. Dominic, with the main compartments and the predella. The three main panels, after the 2007 restoration, are lacking a cornice. And without the modern passe-partout, the painting takes on an appearance which is closer to the original, even if it’s still very difficult to render given the disappearance of the elaborate cornice. The choice of exhibiting the two panels of the predella as well allows you to have a vision as faithful as possible to what the work must have been. In this way, Pinacoteca di Brera offers you the richness and complexity of Carlo Crivelli’s polyptych.

In each guide a single work will be presented in depth. This guide is devoted to the Trittico di San Domenico by Carlo Crivelli.

Support Us

Your support is vital to enable the Museum to fulfill its mission: to protect and share its collection with the world.

Every visitor to the Pinacoteca di Brera deserves an extraordinary experience, which we can also achieve thanks to the support of all of you. Your generosity allows us to protect our collection, offer innovative educational programs and much more.