10 Masterpieces for you

01 - Introduction

Welcome!

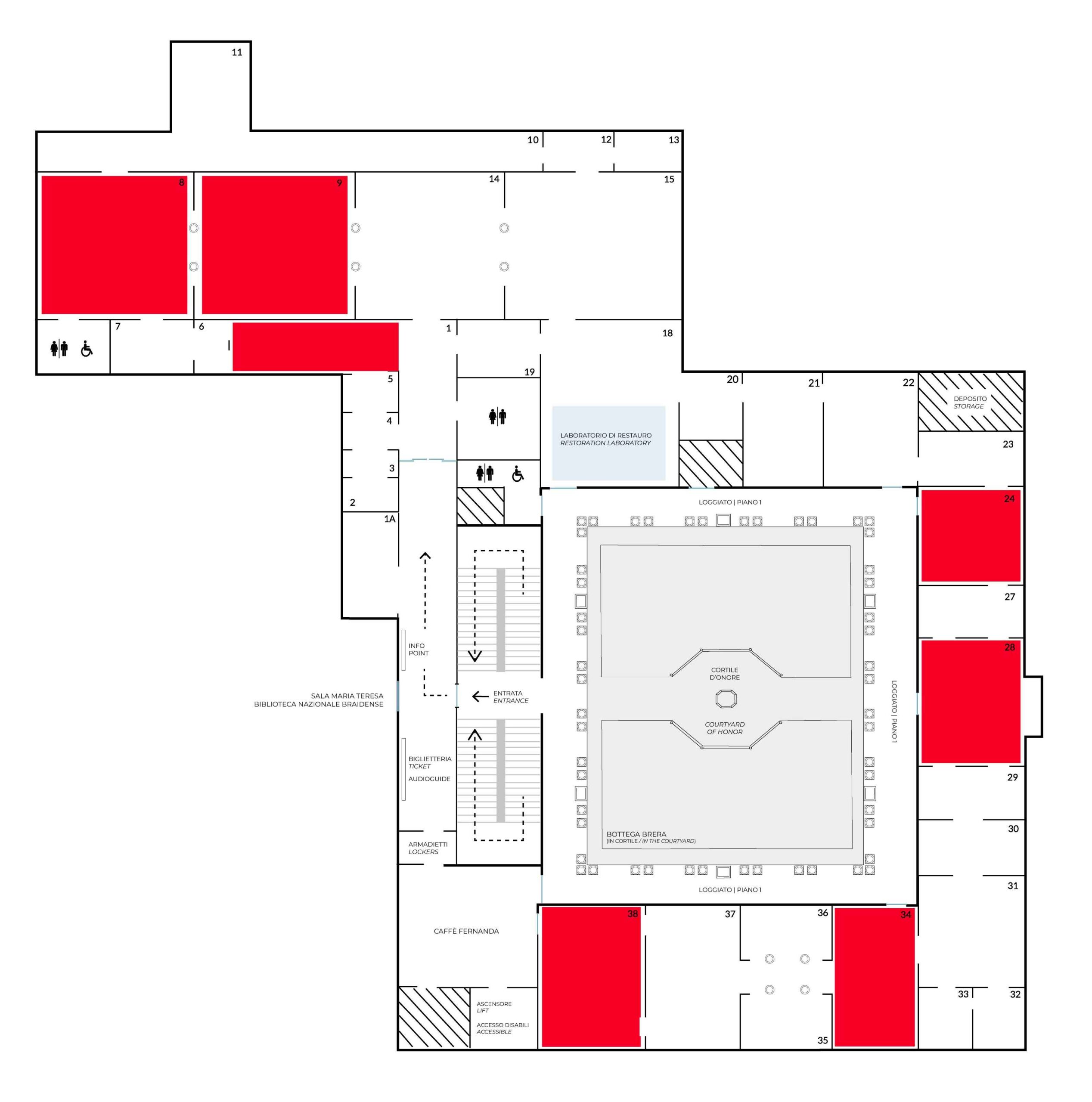

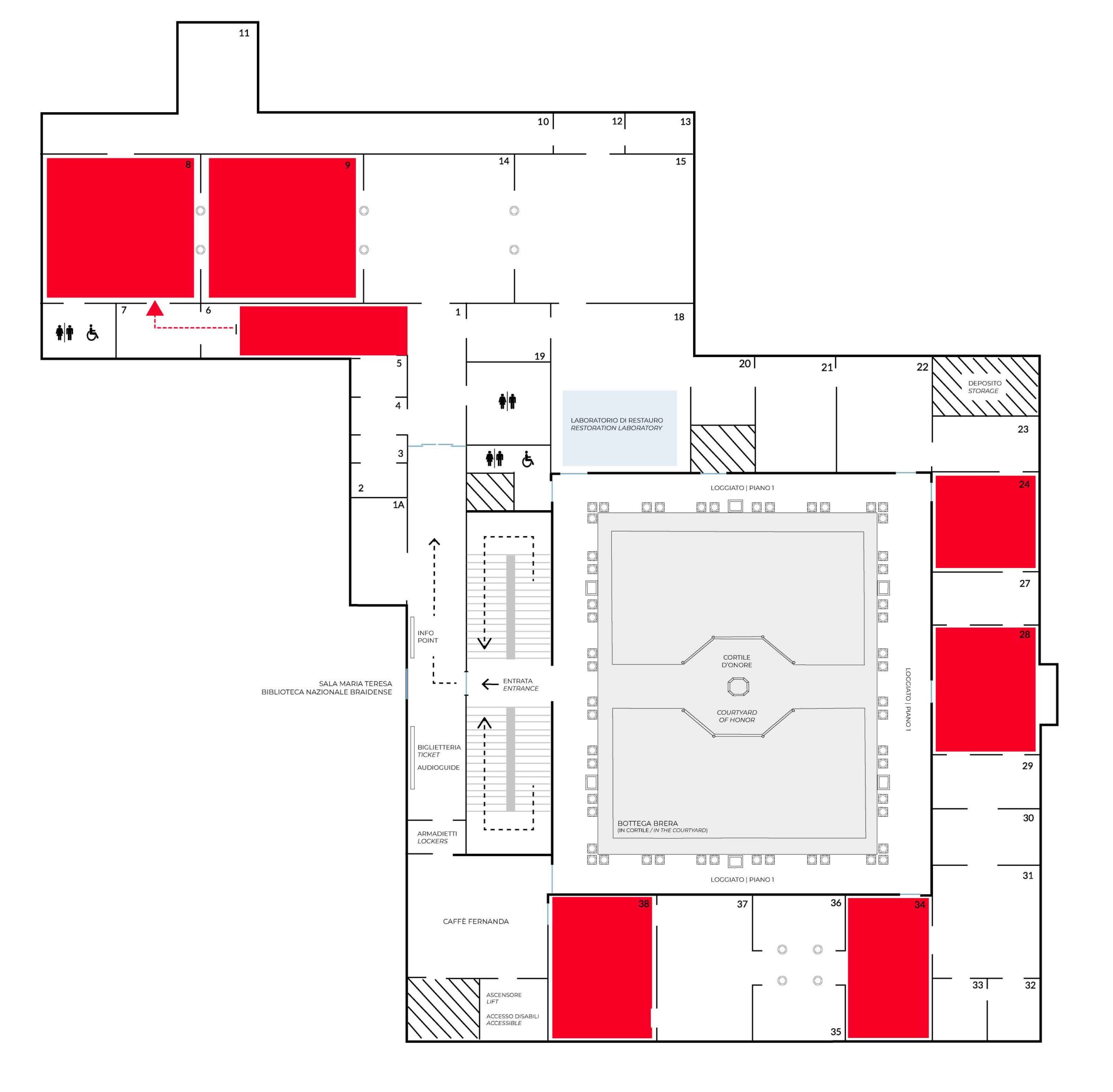

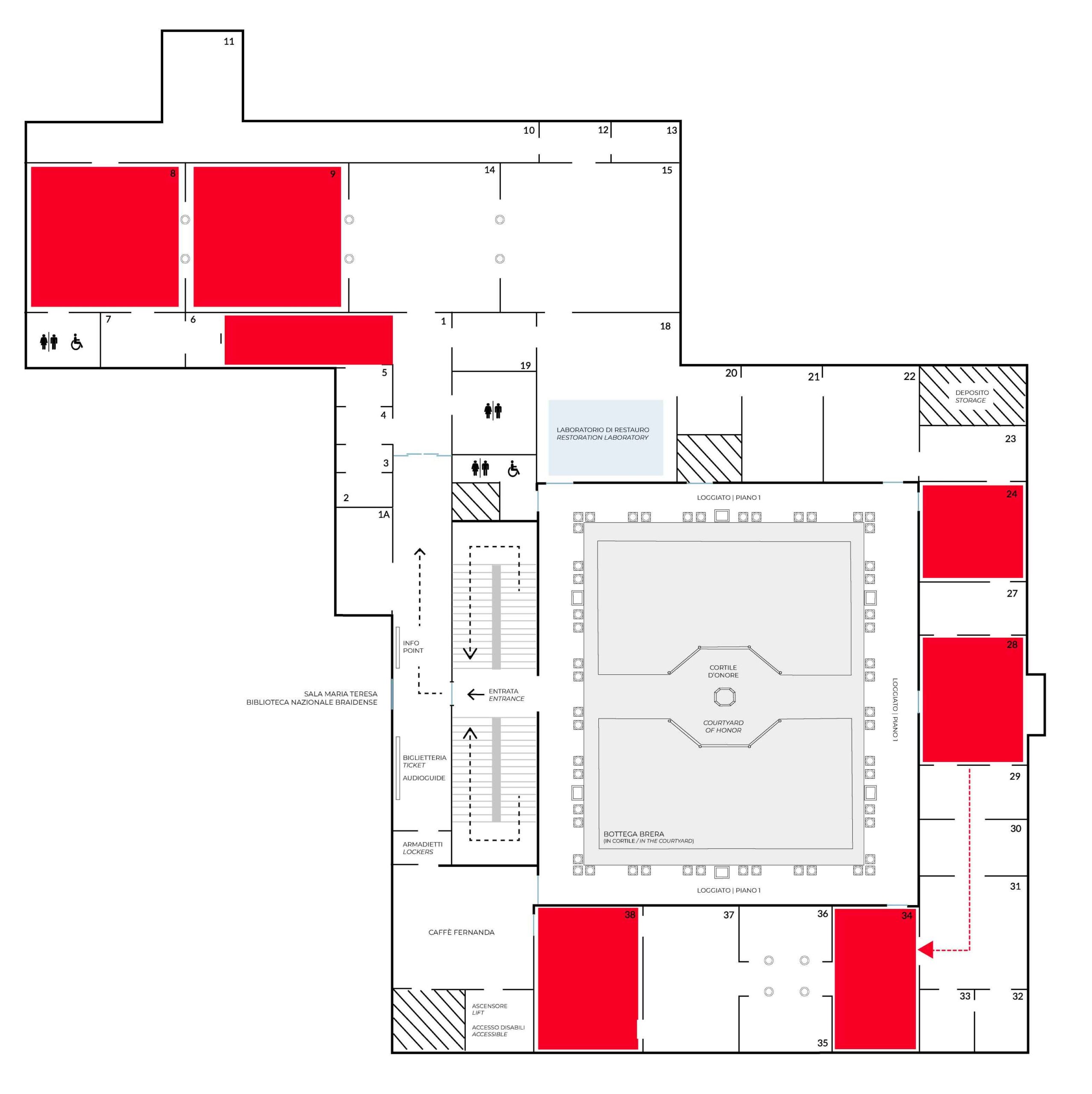

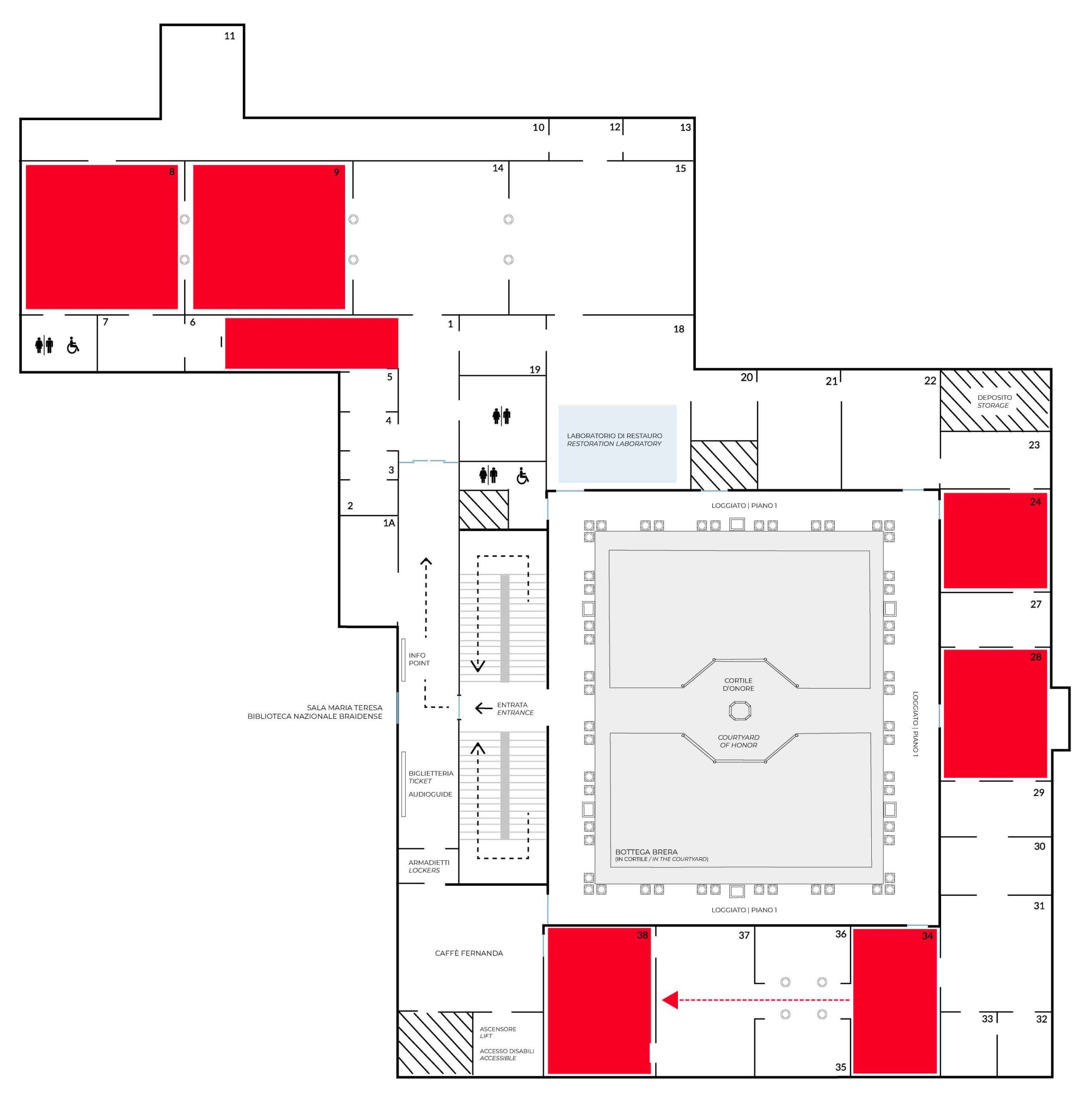

You are about to begin your visit to the Pinacoteca di Brera, whose rooms are all on the first floor of the building. The paintings are displayed in strict geographical and chronological order from the late 13th century to the 19th century. They feature mainly religious subjects because the paintings were originally intended for churches and convents in central and northern Italy.

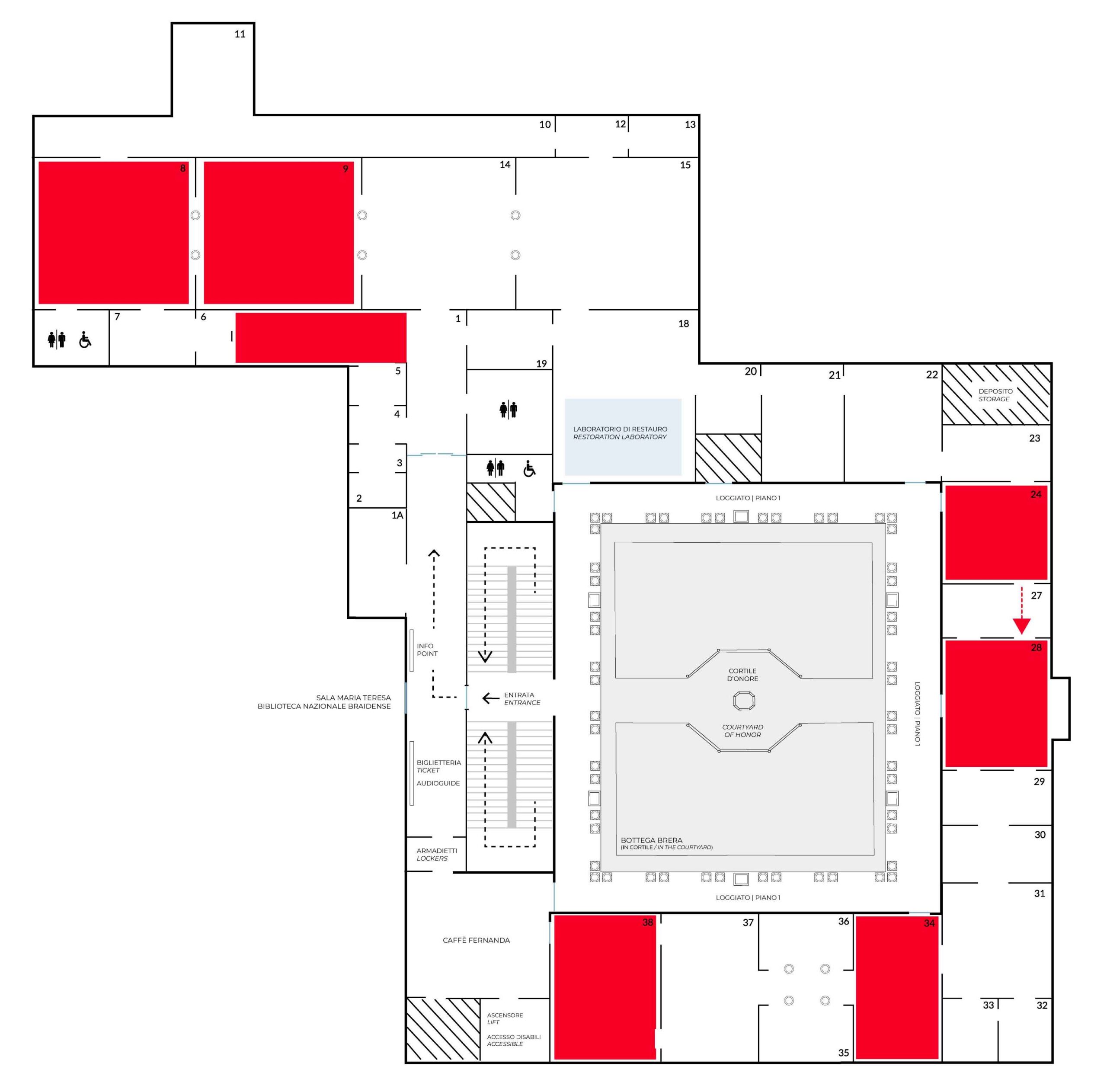

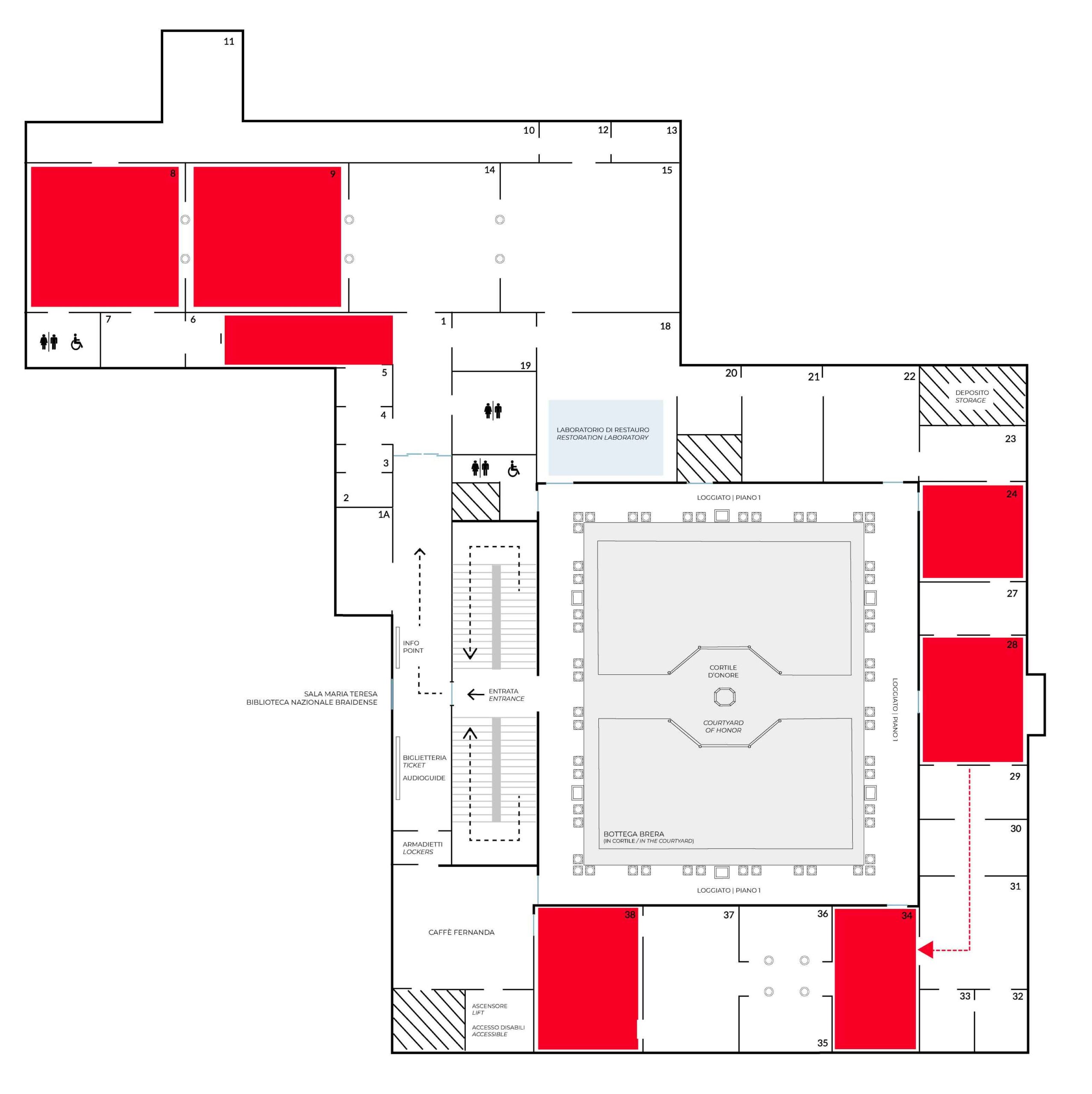

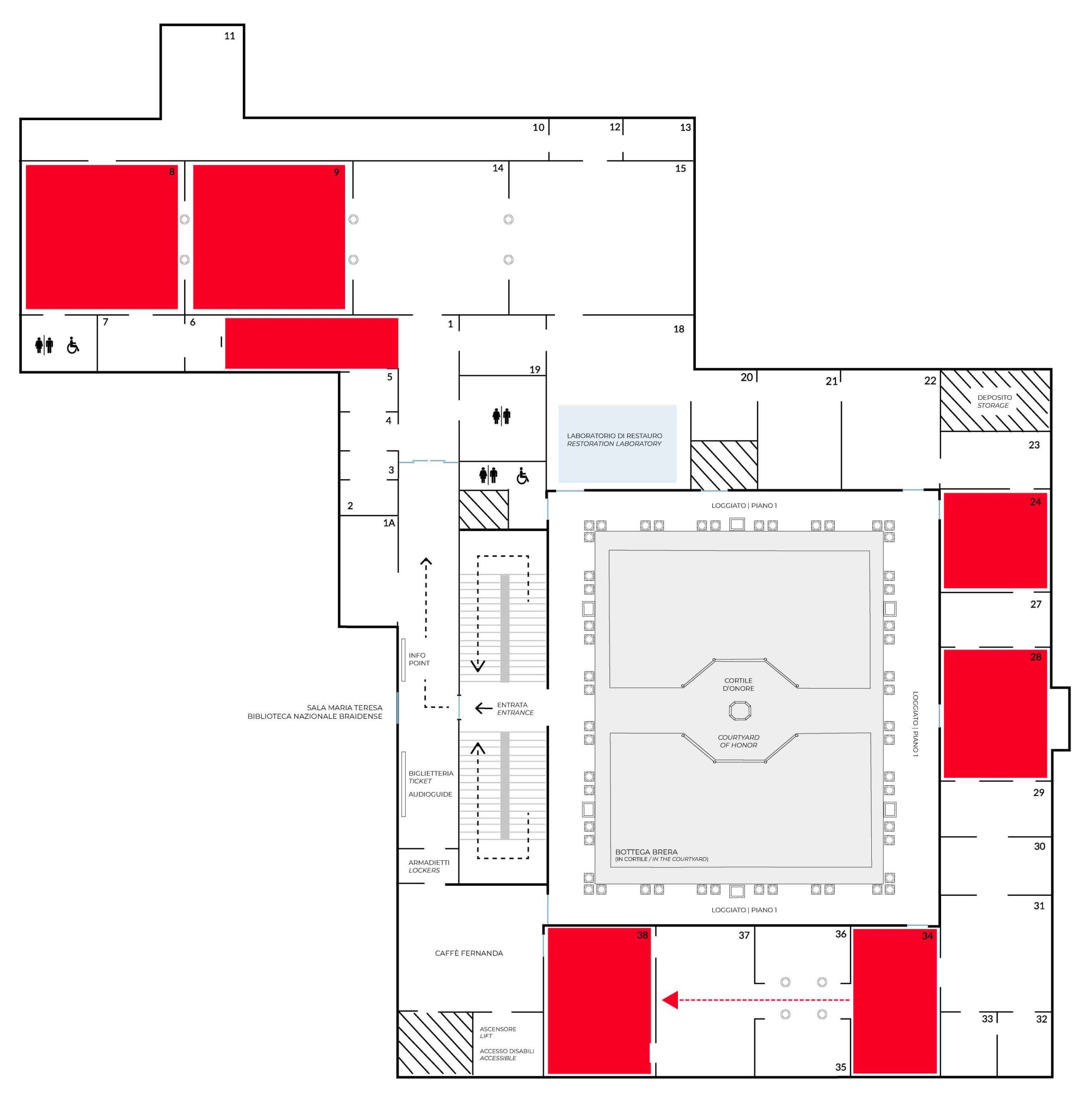

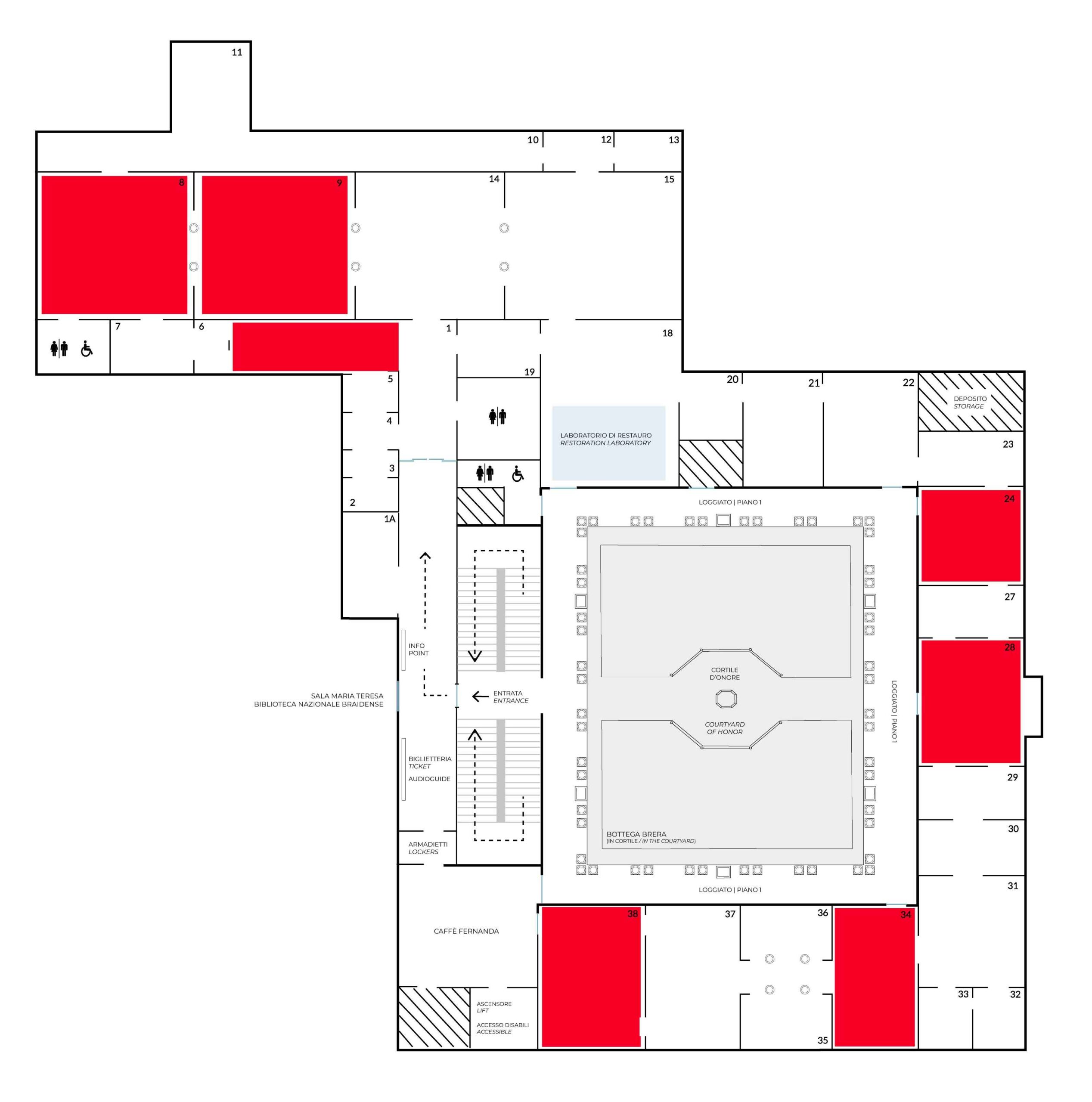

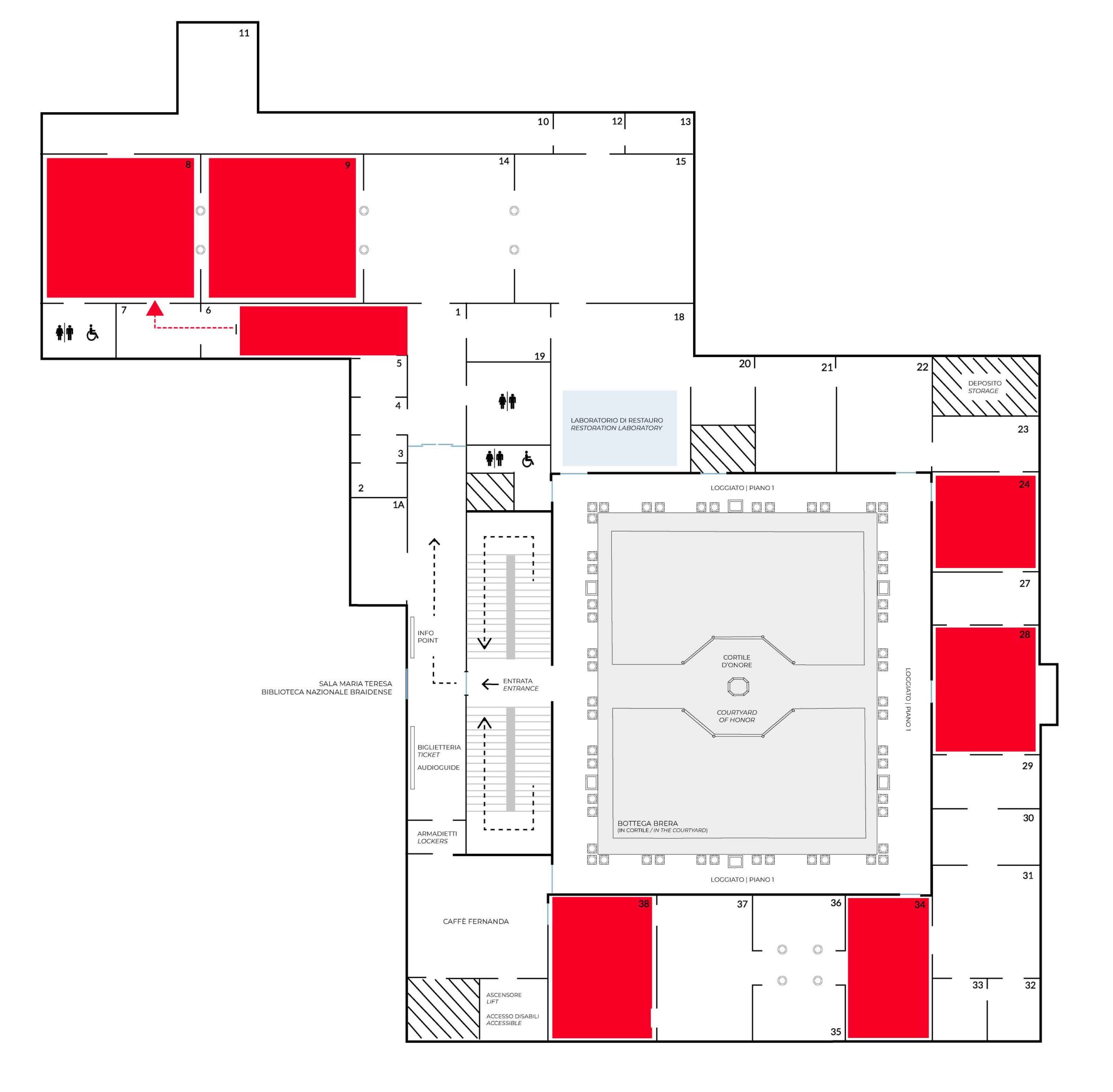

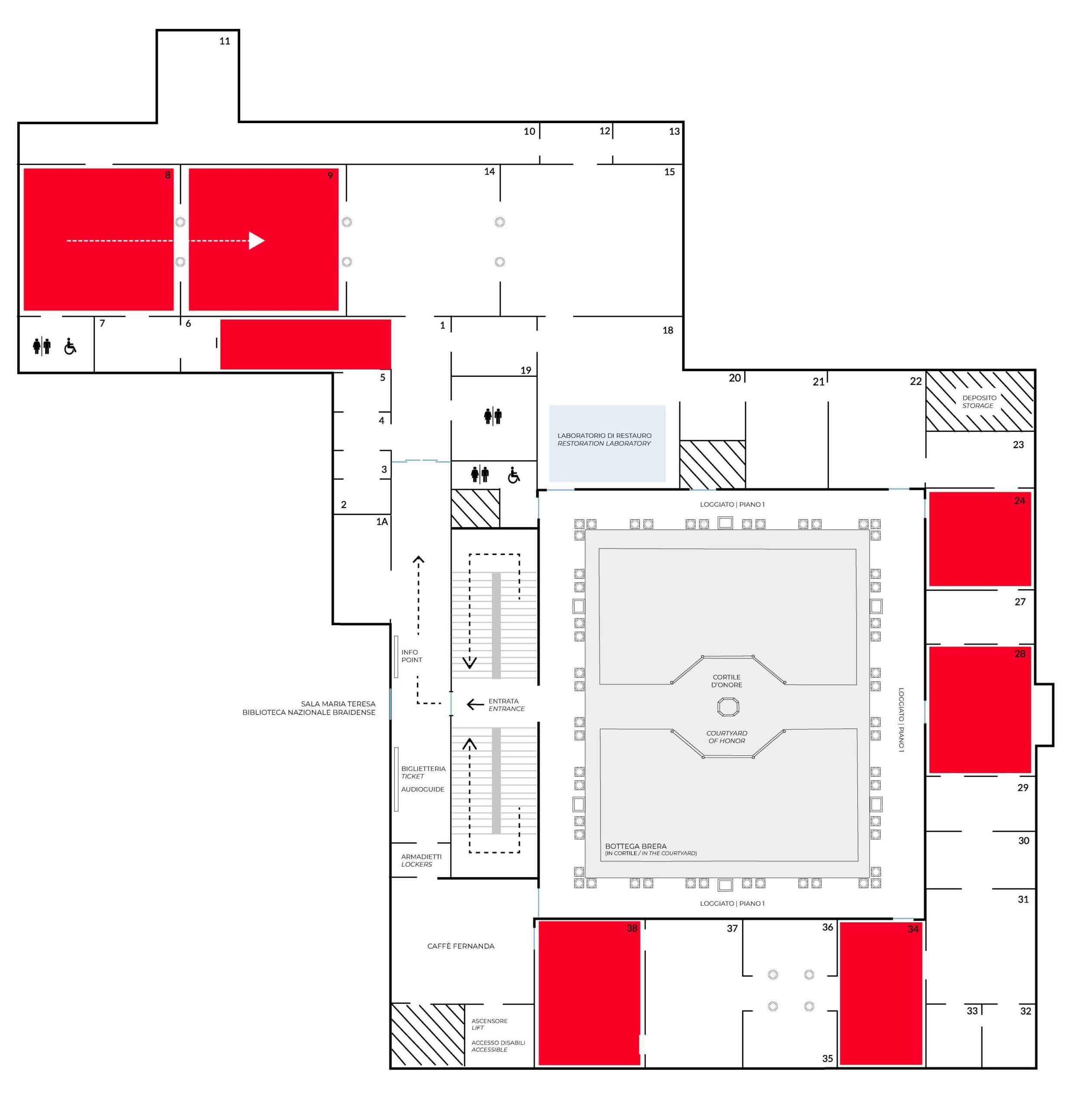

After passing through the entrance to the Pinacoteca – a large glass door – and going down the corridor, you come to room 6 on your left.

This room houses paintings of the 15th century Venetian school on an electric blue background.

The first masterpiece we discuss, Giovanni Bellini’s Pietà, is on the right wall of the room, while the second masterpiece, Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ, is in the center of the room.

02 - Pietà by Giovanni Bellini

Christ is in the center of the painting, with his unarmed hand resting on the front edge of the tomb; the clotted blood seems to rise from the wound along the forearm. The other hand shows the paleness of a bloodless body, accentuated by the contrast with the rosy complexion of the Virgin’s hand. The Virgin, her eyes turned red by tears, draws her face near to that of her Son, perhaps searching in vain for his breath. A split that cannot be reassembled.

Saint John the Evangelist turns his head outward, his gaze lost in his pain, his mouth open. With meticulous truth Bellini describes the muscles, veins and tendons of the dead Christ, unnaturally erect, whom the painter exhibits in all his beauty while the sky, crossed by thin clouds, announces the hour of sunset.

On the left there is a landscape: a road forks towards a castle and a church; also a stream, below, is divided in half, with fast waves that form a whirlpool around a dry tree.

Bellini’s Pietà, donated to the Pinacoteca in 1811 by the Viceroy of Italy Eugenio di Beauharnais, came from the Sampieri Collection of Bologna, where it had been kept since at least the end of the 18th century. Its history before then remains unknown, as is its previous owner, perhaps a very well-educated person. The strip on the tomb contains a reworked version of verses by the Latin poet Propertius, a classical singer of affections: the painter declares that if these painful eyes move to tears the ones who are looking at the painting, the work by Giovanni Bellini itself will be crying. The purpose of his art is therefore to engage the viewer emotionally. Bellini accomplishes this by shortening the distance between the protagonists of the painting and the observer, thanks to the proximity of the figures and the expedient of the hand of Christ that protrudes forward. The gestures and expressiveness of eyes and mouths communicate the relationship of affection that binds the characters, and accentuate the sense of loss. Bellini exalts the expression of feelings that touch deeply, thus revolutionizing the devotional painting of the 15th century and the traditional theme of the Pietà.

The work also marks a change in the painter’s style, distancing itself from the influence of his brother-in-law Andrea Mantegna. A new natural light, for example, softens the incisive and clear contour, typical of Mantegna, and illuminates with reflections the curls of Saint John, the edge of his robe and the mantle of the Virgin.

With this authentic masterpiece Bellini enters the mature phase of his painting, made of light and color, at whose school will feed some extraordinary protagonists of 16th century Venetian painting, from the enigmatic Giorgione to the volcanic Titian.

03 - Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Andrea Mantegna

Christ is lying on the bare stone, half covered by the sheet in which he will soon be wrapped to be laid in the tomb. He has just been anointed with the scented oils from the jar next to the pillow. The wounds were cleaned of the blood, but the flesh pierced by the nails remains open; the hands show their backs and the feet protrude from the stone, pushing into the foreground all the rawness of the Passion.

With his strong presence Christ occupies almost the entire surface of the canvas. At the bottom you can see a bare wall and on the right an opening towards darkness.

The last farewell is entrusted to three characters, relegated to the left corner: John the Evangelist with his hands entwined and his face marked by wrinkles of pain; the Madonna, elderly, with her mouth bent by tears; the Magdalene, whose nose and mouth are only barely visible, opened in a heartbreaking cry. The reflectography which reveals the drawing below showed that the figures of the mourners were conceived from the beginning and the unpainted edges of the canvas confirm that there were no cuts.

Mantegna expressly uses this very engaging close-up shot of a Christ in a daring perspective: in this work he reaches the apex of his research of the foreshortened figure, taking up a theme already addressed in the oculus of the Chamber of the Spouses in Mantua known for the virtuosity of the putti seen from below. Mantegna applied the rules of perspective correctly, but to reach the desired result made some changes; for example, he enlarged the head so it was not smaller than the feet, so that Christ retained his dignity to leave to posterity an image of extraordinary strength.

Even the choice of the technique is essential to the painting’s pathos: a light tempera in which colors combined with animal glue are spread on a thin preparation and made deliberately opaque and dull, thanks to the absence of final varnish.

The history of the painting is complex and still uncertain.

It was probably done around 1483, when a fragment of the stone of Christ’s anointing arrived in Mantua. We know that among the riches in the artist’s studio at his death in 1506 there was a “Cristo in scurto”, that is in perspective, which could be that of Brera. If so, the work would have remained in the painter’s studio for many years, leading some scholars to believe that Mantegna painted it for his private devotion and not for a client. The painting entered the museum in 1824 after Giuseppe Bossi, secretary of the Academy and of the Pinacoteca di Brera, found it in the early 19th century at an antiquarian art dealer’s in Rome.

This work was known and referred to in the painting of various periods, as can be seen in The Finding of the body of St Mark by Tintoretto, exhibited in room 9 of the Pinacoteca. Quotes and suggestions inspired by this work reach up to the 20th century, in the cinema of Pasolini and in the photographs of Che Guevara dead, showing the power of this authentic, immortal masterpiece.

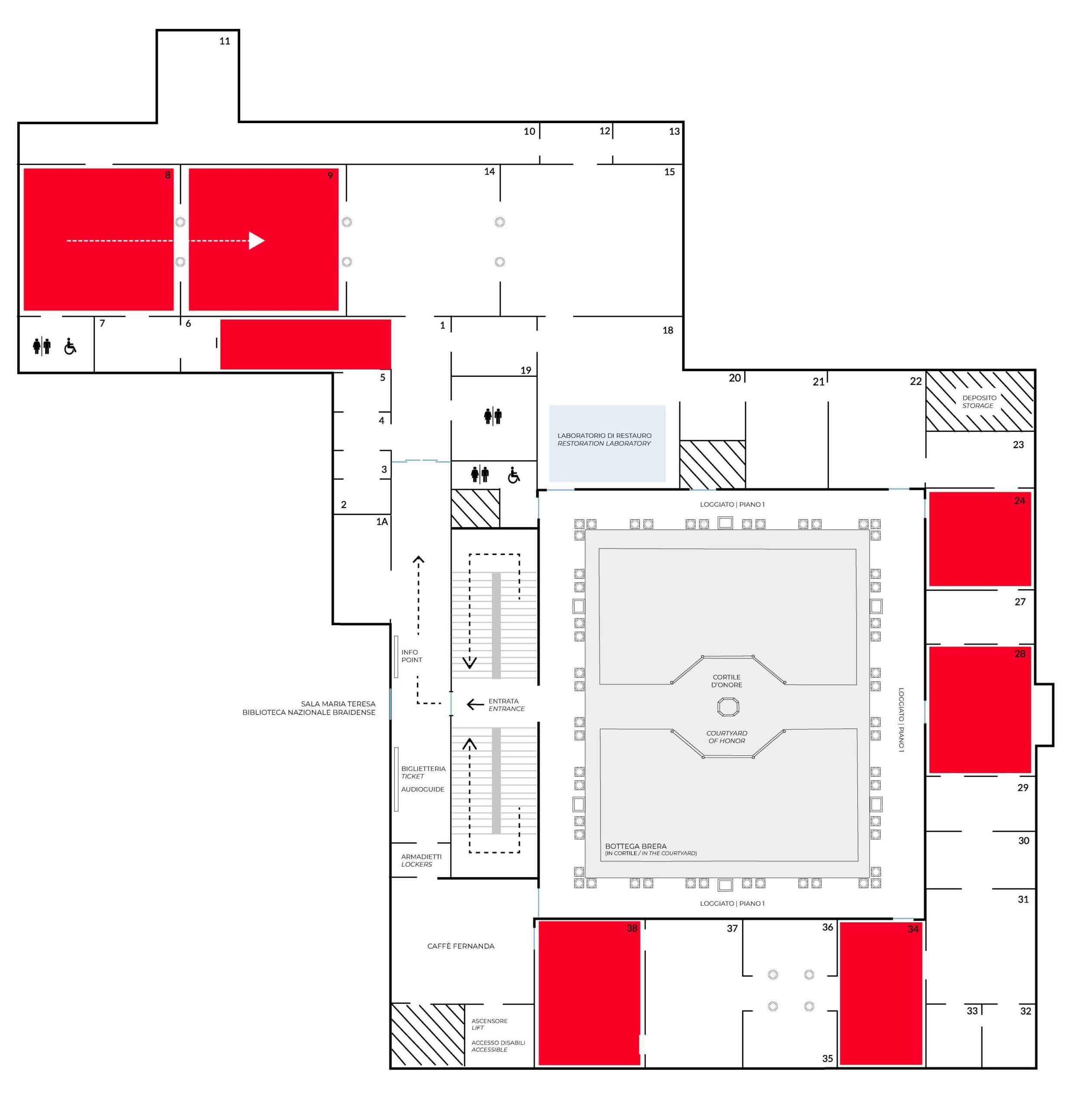

03T - From Mantegna to Bellini Brothers

Leaving rooms 6 and 7, you come to the Napoleonic halls on your right, housing paintings of the 15th and 16th century Venetian and Lombard schools.

This area was once the church of Santa Maria di Brera, but the church was largely dismantled to make way for the museum in the early 19th century. The next masterpiece is in the first Napoleonic hall, room 8.

04 - Saint Mark preaching in a square of Alexandria in Egypt by Gentile e Giovanni Bellini

In a crowded square in Alexandria of Egypt Saint Mark is preaching his last sermon. According to a story of his role in evangelizing Egypt, it was in this city he was martyred.

St Mark is on a podium in the shape of a bridge, while a scribe sets down his words; a man from behind approaches the saint, ready to kill him with the scimitar he keeps in sight. A large crowd – completely veiled women, men with high red headgear and men with large turbans, white as their long scarves – are listening to him. Behind the Saint are the members of the Scuola Grande di San Marco for which Gentile Bellini began this work in 1504. Bellini, who portrayed himself in the foreground dressed in red with a gold chain around his neck, was a member of this important Venetian Confraternity.

In 1507, at the death of Gentile, his brother Giovanni took over, who completed the large canvas: with its 26 square meters, it is the largest painting on canvas on display in the Pinacoteca. According to many art historians it was Gentile who was responsible for the setting of the scene, from the architecture to the arrangement of the characters. The contribution of Giovanni can be read above all in the faces of the members of the Fraternity, which form a series of truthful portraits of the Venetian notables. Among these stands out the self-portrait of Giovanni Bellini, the only figure facing the viewer.

Anachronistically Gentile Bellini sets the episode in a city in Islamic Egypt, where each element contributes to create the atmosphere of a Middle Eastern city. The façade of the building at the bottom of the square, very similar to St Mark’s Basilica, actually looks like a mosque, as suggested by the man at the central entrance, who is taking off his shoes to enter barefoot, and the hexagonal minaret near the palm tree. Next to this building stands what has been interpreted by some as the Lighthouse of Alexandria; next, the so-called Column of Pompey, another Alexandrian monument. On the left stands an obelisk. Next to it is a dromedary, which is not the only exotic animal on the scene: a giraffe is parading in front of the steps of the mosque, while a camel is in the shadow of the second building on the right. The buildings that serve as perspective wings have flat roofs and other elements that qualify them as Middle Eastern, such as small windows, some screened by protruding gratings, carpets laid out on the windowsills, the pitchers hung outside the doors to allow passers-by to refresh themselves. Horizontal bands decorate some houses, as in the first on the left, where there is a portico with round arches, a western architectural element. Gentile therefore gives us an original interpretation of an East that he knew at first hand. In 1479 he was sent by the Republic of Venice to Constantinople to Sultan Muhammad II, to seal the peace reached with the Ottoman Empire: a diplomatic mission entrusted to an artist in times when the importance of a nation was also measured by the merits of its culture.

04T - From Bellini Brothers to Tintoretto

You are now entering room 9, the second Napoleonic hall devoted to the 16th-century Venetian school. You will find the next masterpiece immediately on your right.

05 - The Finding of the body of Saint Mark by Tintoretto

In a dark church Saint Mark appears. He wears the pink robe and the blue cloak, as in the Preaching in room 8. He raises his arm to stop the search for his corpse. His body has already been found and is leaning over the carpet. The three men who drop a dead man from the first grave have not seen anything yet, while a fourth one tries to make light with a candle. Behind the body of Saint Mark a boy is sitting on the ground: he holds himself with a stick and points to his eyes, perhaps to ask for healing. A woman is frightened, not only by the man who grabs her legs, but also by a kind of smoke that comes out of the man’s mouth: it is the devil who, pushed away by the saint’s presence, rises upwards and almost becomes a glowing web that hangs from the vaults. Evanescent characters appear following the wall that, diagonally, moves towards the bottom, where a trap door is open: the shadows created by the lighted torches of those who are still searching underground are visible on the lid.

Next to the saint’s supine body, the patron is down on his knees: it is Tommaso Rangone, Guardian Grande (the chief) of the School of Saint Mark, that is, of the brotherhood dedicated to the patron saint of Venice. According to tradition, in the 9th century the relics of the evangelist were found in Alexandria and then moved to the lagoon city. This work represents the search and discovery of the body of the saint by a group of Venetian merchants.

The painting, completed by 1566, is one of the most famous works by Jacopo Robusti, one of the protagonists of Venetian painting of the 16th century, known as Tintoretto after the profession of his father, a cloth dyer (tintore in Italian).

Outside his workshop, Tintoretto put up the sign “Colour of Titian, drawing of Michelangelo”. This anecdote gives us the idea of his great ambition: to be a synthesis between Titian, the highest representative of Venetian painting, dominated by color, and Michelangelo, the highest interpreter of Florentine painting, based on the primacy of drawing.

In the work at Brera the muscular body of the saint shows the suggestion of Michelangelo’s model.

Tintoretto skillfully applied perspective both to individual figures, for example to the supine body of the saint, and to the overall scenario, with the vanishing lines converging on St Mark’s open hand emphasizing his peremptory gesture. The diagonal perspective is accompanied by the sequence of the vaults, illuminated by the flashes of light that Tintoretto used to enhance the drama of the scene. The painter used to build miniature theaters in which he put small figures to try out the positions, attitudes, drapery of the characters, but also used candles to check lights and shadows. He then moved on to drawing and finally to colour, the last phase of a complex creative journey. The speed with which Tintoretto laid the brushstrokes, for which he was often criticized, as if it meant a hastily thought out and almost arrogant practice, is also the result of an extraordinary creative urgency that helped to make his figure very close to modern sensibility.

05T - From Tintoretto to Piero della Francesca

As you walk through the rooms, you will see the colossal plaster statue of Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, the bronze version of which you have already encountered in the Palace’s courtyard of honour. The statue, cast from Antonio Canova’s marble model, is displayed here to celebrate the opening of the Pinacoteca on 15th August, 1809. It was in those years that Brera was converted, at Napoleon Bonaparte’s behest, from a picture gallery reserved for the students of the academy into a major national gallery open to an ever-growing audience.

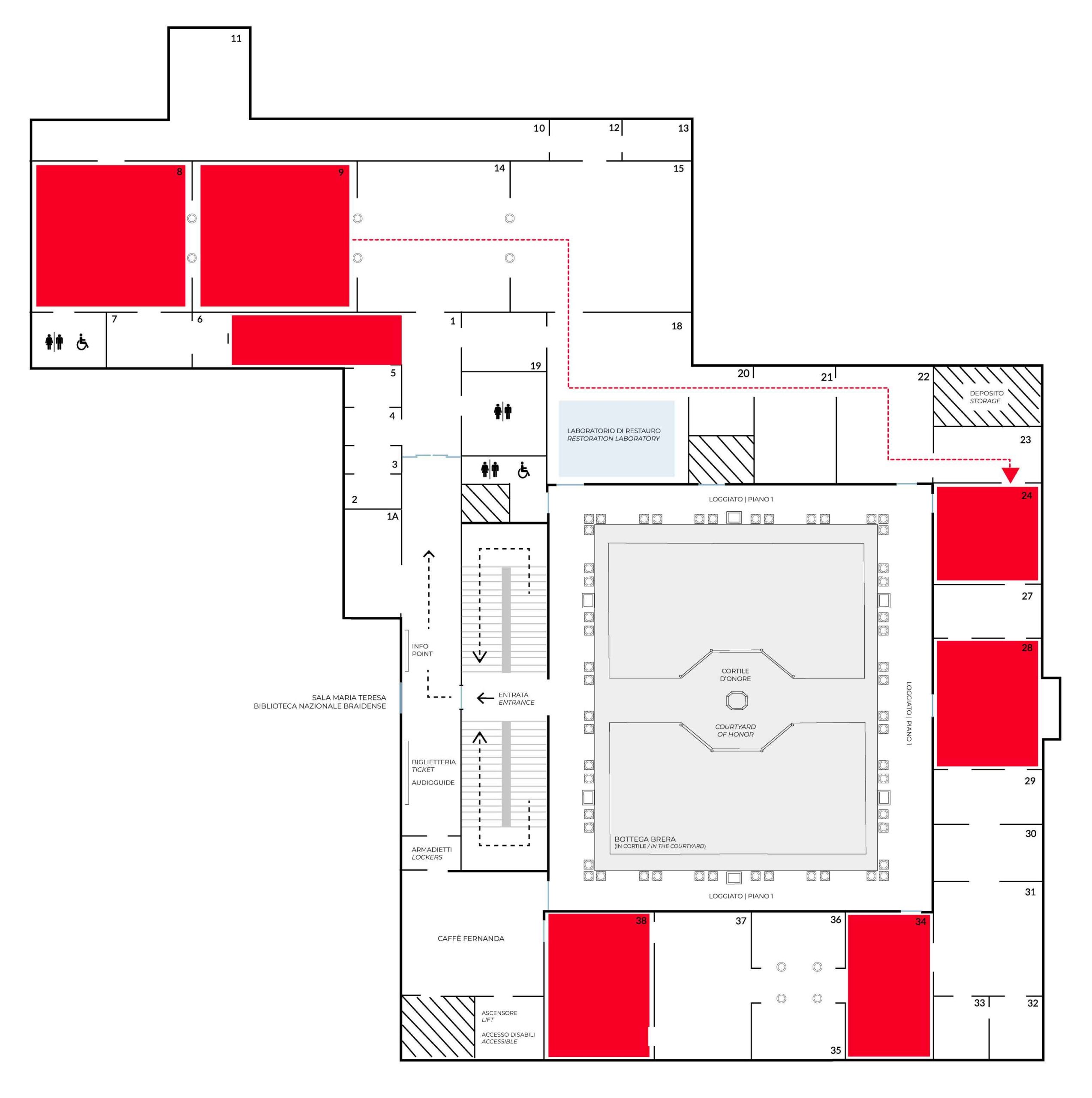

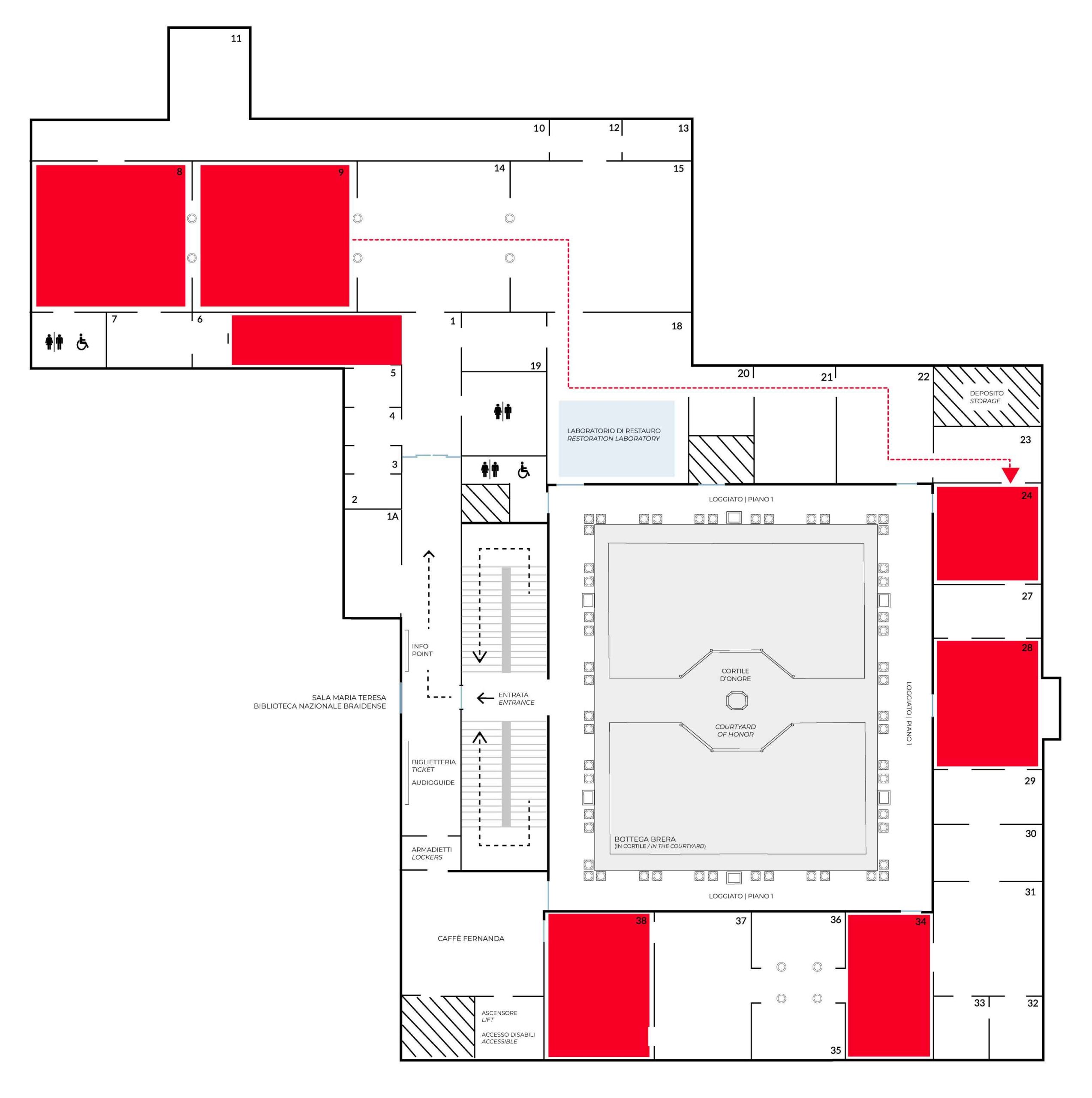

Proceeding on the tour, you enter room 18 which houses our restoration laboratory, where the museum’s restorers study and care for the paintings in the collection, often under the gaze of visitors. The laboratory was designed by Sottsass Associati.

As though conducting a journey from northern to central Italy, you have admired paintings from the Veneto and Lombardy in the Napoleonic halls and paintings from Emilia and the Marche in the red rooms. Now, past the on-site storage facility, the journey takes you all the way to Urbino in room 24. All the paintings in this room are closely linked to the court of Urbino, an important centre in the development of Renaissance art.

Here you will find the next two masterpieces on this tour.

06 - The Montefeltro Altarpiece by Piero della Francesca

The Madonna sits in the middle of an orderly group of saints and angels;

her eyes are low and her hands are joined while she is holding Jesus asleep on her lap. On his knees is the patron Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino. He wears armor with a cloak; the sword is tied to the belt, the knobs, the stick and the helmet are resting on the ground. The last-named object bears the trace of the blow suffered during a tournament that had made him one-eyed, forcing him to be portrayed in profile. The characters are in a classical church with walls decorated with polychrome marble slabs. The barrel vault that covers the apse is punctuated by ceiling coffers, which give depth to the space, and it is decorated with a large shell from which hangs an egg attached to a small chain.

The work arrived in Brera in 1811 from the Church of San Bernardino, just outside Urbino.

The date of the painting’s creation is still uncertain. One of the hypotheses is that Piero painted it around 1472, the year in which the ducal heir Guidobaldo was born, but Federico’s wife Battista Sforza died. In that same year Federico, an educated man who earned his wealth as a captain of fortune, conquered Volterra on behalf of Florence. Some elements in the canvas would confirm this reading: the Duke’s armor, worn as if to celebrate the recent victory; the choice to include John the Baptist, the first saint on the left, to commemorate his late wife Battista, who is absent in the painting; the shell and egg, symbols of birth, would be placed to greet the arrival of Guidobaldo.

To the meanings linked to the life of the Montefeltro family, devotional ones are added: the sleep of Jesus and his necklace of blood red coral refer to the Passion; the shell and the egg instead remind viewers that Jesus will be reborn on the day of Resurrection. The egg, a model of geometric perfection, is the symbolic center of the painting. It seems suspended above the head of the Madonna but, if you look more carefully, you will notice that the figures are in fact in front of and not inside the apse. The egg is therefore far away, and of considerable size: it is an ostrich egg.

According to a medieval belief, the ostrich abandons her egg in the desert, where the sun fertilizes and broods over it; its presence in the painting could allude to the Virgin, who became a mother thanks to the Holy Spirit.

The particular ability of Piero to compose such solemn and convincing spaces comes from his study of mathematics and perspective. His passion for the mathematical sciences, together with his interest in the effects of light on objects, are the hallmarks of his style.

In the painting, the light comes from a source we see reflected on the shoulder of Federico’s armor, an arched window, and perhaps a small oculus. Referring to the Flemish art known at the court of Urbino, Piero captures the sheen of the diadems of the angels; he renders the transparency of the angel’s robe to the left of the Virgin and the crystalline cross of Saint Francis, who opens his tunic to show the wound in his chest.

The silent figures with quiet gestures, who inhabit a space immersed in a suspended time, make this work not only a masterpiece of Renaissance culture, but an eternal mystery of beauty.

07 - Marriage of the Virgin by Raffaello Sanzio

In the large square in front of the temple, Mary and Joseph marry in the presence of the high priest who joins their hands. Accompanied by her maids of honour, the Virgin receives the ring from Joseph, as described in the apocryphal Gospels and in the Golden Legend, a medieval text that collected the lives of the saints. In these sources it is said that, inspired by God, the high priest of Jerusalem asked Mary’s suitors to each come to the temple with a dry twig. Among them Joseph was chosen, because his twig miraculously bloomed once laid on the altar of the temple. Behind him there are five other suitors who keep their twigs with no flowers: in the foreground one of them breaks the rod with his knee, while another, just behind, more discreetly bends it with apparent carelessness.

At the center of the square, marked by the sequence of perspectival paving slabs, there is a sixteen-sided temple with a double open door. The view thus penetrates beyond the harmonious architecture by following the vanishing lines of perspective.

Above the central arch of the temple the signature appears: RAPHAEL URBINAS, and the date in Roman numerals, 1504.

Raphael was born in Urbino in 1483. At the age of around twenty, he was commissioned to carry out this work for the Chapel of San Giuseppe in San Francesco church in Città di Castello. Probably the clients had asked him to take as a model the Marriage of the Virgin by Perugino, painted in those same years for the chapel of the Perugia Cathedral that housed the alleged relic of the Virgin’s wedding ring.

The comparison with the work of Perugino, today at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Caen, shows how the young Raphael was already able to change the course of Renaissance art. The central plan temple, which in Perugino is a background looming over the characters in the foreground, becomes in Raphael the pivot from which originates a space that expands towards infinity. Raphael doubles the sides of the temple of Perugino and creates a portico supported by Ionic columns. The curve of the dome is recalled by the figures in the foreground who are not lined up, as in Perugino, along a hypothetical horizontal line, but ordered in semicircles which can be seen by looking at the feet of the nearest characters, aligned along a regular curve.

Raphael shows himself to be a true master of rhythm and geometry, and paints a very calibrated composition, studied in every detail, but communicated with extreme grace and naturalness. In the same way, the young master chooses the colours, playing with similarities and contrasts whose perfect balance increases the fame that rightly accompanies this work.

07T - From Raffaello to Caravaggio

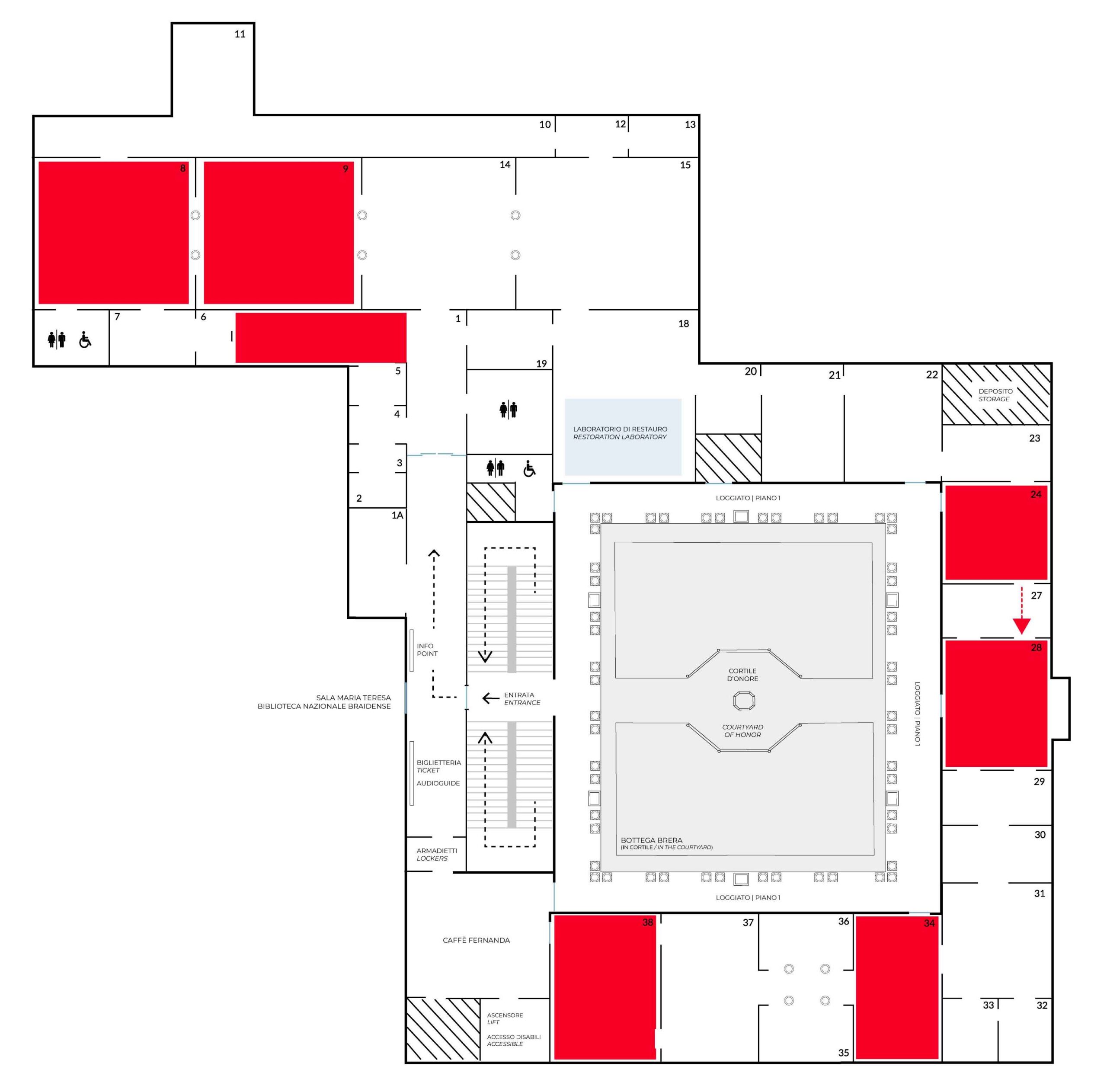

Room 24 was once divided into three small rooms, which is why the rooms immediately after it are numbered 27 and 28. Room 28 houses 16th and 17th centuries paintings from the area of Bologna and central Italy. The next masterpiece sits between the two arched openings.

08 - Supper at Emmaus by Caravaggio

In a setting dominated by darkness, light comes from the left to illuminate the scene. Christ is blessing the newly broken bread. His gaze is downward, and his face is slightly inclined. The man in profile juts out his neck and frowns, leaning forward to better see what is happening as if he does not believe his eyes, while the other, from behind, shows his amazement with raised and open hands. The innkeeper, who looks perplexed, and the servant, on the contrary, remain strangers to the event because they do not recognize the gesture of Jesus. On the table are a few elements: two loaves, a ceramic plate with herbs, a pewter plate and a carafe. Just behind, a glass of red wine.

The moment depicted concludes the episode described in the Gospel of Luke, in which two disciples walk part of the way from Jerusalem to Emmaus with a traveler, to whom they confide their sadness at the death of Jesus. When evening comes, the disciples invite the man to have dinner with them in an inn. Only when they see him blessing and breaking the bread, repeating the gestures of the Last Supper, do they understand that he is the Risen Christ. Immediately afterwards he disappears from sight.

Caravaggio stages the moment of the unexpected revelation. Christ is depicted with his face half immersed in the shadow into which he will immediately disappear.

Caravaggio painted the canvas at a crucial moment in his life. In May 1606 he killed a rival in Rome. Waiting to know his fate, he fled to an estate outside of town, between Paliano, Zagarolo and Palestrina, perhaps protected by the powerful Colonna family. But he did not stop painting. He made this canvas in hiding. It is the second version of a theme that he had already addressed a few years earlier in another painting now exhibited at the National Gallery in London.

Sentenced to death, Caravaggio was then forced to leave the Papal States, thus beginning the last troubled phase of his life.

The skill with which Caravaggio uses light and shadow painted in earthy tones gives the Brera version an intimacy and lyricism lacking in the more theatrical version of London. The work represents a turning point in Caravaggio’s style, characterized by a greater attention to the expressive and dramatic charge of the scene, all focused on the characters and the very few objects surrounded by darkness. Light tells that a revelation had occurred. The shadow rests on bodies and things represented truthfully; it emphasizes gestures and expressions; it crosses the face of a Christ veiled with melancholy; it enters the furrow of the bread irregularly broken, true to the plainness that Caravaggio brought with him from his education in Lombardy.

The painting, which entered the Pinacoteca in 1939 thanks to the contribution of the Friends of Brera Association, is one of the only two works by Caravaggio in Milan; the other is the famous Canestra di frutta [“Basket of Fruit”] at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

08T - From Caravaggio to Tiepolo

The following rooms, up to room 33, house examples of 17th century painting, while room 34, devoted to the art of the 18th century, hosts, among others, the first paintings ever to have joined the Brera collection. There is also a large canvas by Tiepolo, our next masterpiece.

09 - Our Lady of Mount Carmel by Giambattista Tiepolo

This canvas, an early work by Giovan Battista Tiepolo, was commissioned in 1721 for the chapel in Sant’Apollinare in Venice by the members of the Confraternity of Suffrage, visible in procession in the background while they walk solemnly and hooded towards the Madonna carrying lighted candles. The church was officiated by the Carmelites, which explains the choice of the characters and images represented.

The painting has a singular history: after the requisition from the place of origin in the Napoleonic age, it was cut into two parts and sold. Until the middle of the 20th century the scene on the left with the souls of Purgatory remained divided from the sacred group on the right. Only later the two pieces – which had been donated to Brera separately in 1925 – were stitched together.

The story highlights a significant fact: the work is composed of two opposing parts.

On the right, Mary and Jesus, the luminous cornerstones of the composition, are lit by bright colors and give light to those who contemplate them closely.

Our Lady offers the scapular to Saint Simon Stock, appointed in 1245 General of the Carmelite Order, kneeling before her. The scapular is a strip of cloth hanging on the chest and on the back with an opening for the head and the hood typical of the dress of some religious orders. The delivering of the scapular to Saint Simon during a legendary apparition of Our Lady was accompanied by the promise of salvation for those who had worn it until their death.

Albert of Vercelli, who was the first to set the Rule of the Order, takes part in the scene. On her knees is Saint Teresa of Avila who, filled with ardor, throws herself almost on all fours to the steps, from which the Madonna and Child rise, as at the top of a triangle. The saint rightly appears in a painting that includes the most eminent Carmelite figures, since in the 16th century she was a reformer of the Order and founder of the Discalced Carmelites. On the right in the background the prophet Elijah prays in clouds with cherubim. His presence is not surprising because on Mount Carmel in the Holy Land some of his followers had begun communities of hermits, considered to be the origin of Carmelite spirituality.

Jesus holds in his hand an object of popular devotion: the small scapular, composed of two rectangles of cloth to be worn in contact with the skin. The scapulars therefore indicate a relationship of closeness with Our Lady of Carmel whose protection is asked against the dangers and defense from the sufferings of the Afterlife; the Brotherhood of Suffrage, which commissioned the painting, was engaged in particular in the intercession for the souls of the deceased.

In the left part of the painting, in stark contrast to the luminous appearance on the right, the souls of Purgatory are depicted in dark tones characterized by a dramatic chiaroscuro. A man who would like to leave the depths in which half of his body is still sunk clings to the angel in flight.

An incandescent glow reddens the smoke rising from the earth next to the boy with his face towards us. The young man with a muscular back seems to come out of a hole, stretching his arms, with joined hands towards the protagonists of the sacred story. In the background other people drown in the shadows.

The ability to dramatize the scene, accentuated by done-on-purpose contrasts and the dynamism of numerous diagonals, makes this work a masterpiece of Tiepolo who, not yet thirty, is about to become one of the most brilliant protagonists of European painting of the 18th century.

09T - From Tiepolo to Hayez

You are now passing through the corridor between rooms 35 and 36, which offer a glimpse into the painting of the 18th century in the Veneto and Lombardy, including work by Canaletto, Guardi, Fra Galgario, and Pitocchetto. Room 37, on the other hand, is devoted to 19th century painting, as is room 38 which houses the last two masterpieces on this tour.

10 - The kiss by Francesco Hayez

Two young people, held in an embrace, kiss passionately. She puts her hand on his shoulder and he holds her head to pull it towards himself. Their faces are almost completely hidden, while their lips touch. It seems to be a farewell kiss, since the young man, ready to leave, already has a foot on the step.

A threat seems to loom over them: the shadow of a person on the wall on the opening to the left is disturbing. They may be located in the entrance hall of a castle; on the upper right is the lower part of a dark window.

The theatricality of the pose of the protagonists is rendered with studied spontaneity. The girl’s blue silk satin robe draws attention; its shine recalls the best Venetian pictorial tradition, of which Hayez, born in Venice, was considered the last representative. The young man’s characteristic hat is worth considering: worn by Italian patriots, it suggests the political meaning of the painting linked to the Risorgimento.

The extraordinary nature of the work is achieved by the original interpretation that Hayez gives to a daily fact like a kiss between lovers. The setting is medieval, as indicated by the clothes and the original title (The kiss. Episode of youth. Costumes of the fourteenth century), but the ardor of the gesture is completely modern. This is not the simple triumph of youthful passion; the painting is in fact a symbol of those who must fight for the nascent nation, fragile as this love just blossomed, besieged by shadows offstage. The artist creates an authentic manifesto of the struggle for Italian independence, won even at the cost of the sacrifice of the deepest affections, for the good of the homeland.

Commissioned by Count Alfonso Maria Visconti who later donated it to the Pinacoteca, The Kiss was presented in 1859 at the Exhibition of the Brera Academy of Fine Arts three months after the triumphal entry into Milan of Vittorio Emanuele II and Napoleon III. The Second War of Independence had just ended, and Milan and Lombardy had been freed from Austrian rule.

Francesco Hayez was then almost seventy years old and was among the most celebrated masters of the time, the greatest exponent of historical Romanticism in painting.

Thanks to the success that immediately accompanied the painting, the prints that reproduced it multiplied, as shown by the work of Gerolamo Induno, Doleful premonition, exhibited in this room next to The Kiss. We are in 1862. In a humble room a girl looks at a miniature of her boyfriend. He left as a volunteer and she seems to feel that he will never return. Together with other symbols of the Risorgimento, in the room there is a reproduction of the now famous Kiss.

In the 20th century Hayez’s painting maintained its popularity, even if deprived of its historical meanings: it was mentioned in the film Senso by Luchino Visconti; inspired the image of the “al bacio” (perfect) lovers on the boxes of a famous brand of chocolates; and was the protagonist of reinterpretations by street artists and of parodies by cartoonists.

From a celebrated Risorgimento icon to an extraordinary pop icon: tangible proof of the inexhaustible vitality of this masterpiece.

11 - "After Lunch (The Pergola)" by Silvestro Lega

It is a serene summer day after lunch. The light brightens the fields and fades the poplars on the horizon, immersed in a white sky of heat. A pergola shelters some women and a child from the heat. A woman, with maternal confidence, puts a hand on the shoulder of the child who tells something with lively gestures. Another, in front of her, is listening to her quietly, while she holds her head with her hand. The woman with the open fan turns while the coffee is coming, brought on a tray by a woman with an apron. On the bench at the bottom, cups are ready. On the wall to the right is an orderly row of terracotta pots with white and red flowers; some unruly flowers have escaped from the largest vase and now, exuberant, grow at its base. Among the light tiles of the pavement appear sparse tufts of tenacious green sprout.

The painting by Silvestro Lega, known as The Pergola or After Lunch, was donated in 1931 to the Pinacoteca by the Friends of Brera Association. It’s signed and dated at the bottom left. It was made in 1868 in Piagentina in the hills outside Florence, where the painter from Romagna had retired after a few years in the Tuscan capital. The period of Piagentina was the most peaceful of the life of the painter, a guest of the Batelli sisters. With one of them, Virginia, he had a love affair, abruptly interrupted by her death from consumption. The liveliest works by Lega belong to the 1860s: airy scenes en plein air in a relaxed and serene countryside, and simple interiors that tell the poetic everyday life of family affections.

The clear palette, the purity of the line, and the sharpness of the composition show the personal reworking of Tuscan painting of the 15th century.

The work coincides with the most fruitful years of ‘Macchiaioli’ painting in Italy, which numbers Lega among its protagonists. The ‘Macchiaioli’ movement, born before French Impressionism, brought together artists who aimed for the truth of visual perception through using ‘spots’ (macchie) of colour, with contrasts between light and shadow without gradual steps.

It is precisely the alternation between light and shadow that gives a unique personality to this masterpiece by Lega. Warm rays of sunlight overcome the barrier of the pergola by painting light stripes on the ground; they brush a white spot on the shoulder of the woman on the bench; and they illuminate small parts of the girl’s face and dress. The light turns some of the leaves of the climbing plant yellow, but it cannot reach the most hidden ones, which remain dressed in full green thanks to the shade in which they rest. The half-light surrounding the figures creates an atmosphere of calm family confidence. A fleeting moment of light and color, but also of looks and gestures, that the art of Lega captured forever in this masterpiece of the Italian 19th century.

10 Masterpieces for you is an audio guide available free of charge on the museum’s website and app, which takes you along the Pinacoteca’s route and invites you to pause for a few minutes on the collection’s major masterpieces.

Support Us

Your support is vital to enable the Museum to fulfill its mission: to protect and share its collection with the world.

Every visitor to the Pinacoteca di Brera deserves an extraordinary experience, which we can also achieve thanks to the support of all of you. Your generosity allows us to protect our collection, offer innovative educational programs and much more.