Third dialogue “Caravaggio. Readings and Re-readings”

The Pinacoteca hosts the new exceptional dialogue between the museum’s most celebrated paintings, the Supper at Emmaus by the Lombard master Michelangelo Merisi, better known as Caravaggio and other “guest” works.

For the occasion, and to tie in with the renovation of the layout in seven of the Pinacoteca’s rooms, the painting is to be hung in a new scenographic and much less out-of-the-way position than previously, in an effort to higlight the outstanding chiaroscuro effects of this picture which the artist painted at one of the most dramatic moments in is life, while he was fleeing Rome in 1606 after slaying Ranuccio Tomassoni in a brawl on 28 May of that year. The painting can be dated to some time during the four months following the event, when Caravaggio was staying on the Colonna estates, and it was probably painted at Paliano. Its brushwork displays such immediacy and such rapidity that the underlying sizing shows through in certain areas, and some of the details even have an “unfinished” or summarily sketched appearance to them. The painter also adopts certain solutions that were to feature with ever greater regularity in his work after he fled Rome, displaying an increasingly painful and deeply-felt sense of being and existing, and of what it really meant to “paint”.

A Question of Attribution

Caravaggio: “A question of attribution“, curated by Nicola Spinosa, will be offering visitors a chance to compare a number of paintings of the same subject which have never been displayed together before. But at the same time, it sets out to be a workshop and a source of stimulus for exchange and further study of this artist, whose career continues to pose crucially problematic questions to art historians while at the same time stirring a huge amount of interest with the general public.

So we are looking at a comparison designed both to promote scholarship and to encourage broader appreciation by submitting a number of attribution issues regarding the works on display to the attention of scholars and visitors alike. The Brera Supper at Emmaus will be interacting with five paintings whose attribution to Caravaggio has been given a mixed reception or been questioned, or which have been attributed to other painters who were Caravaggio’s contemporaries.

They include three paintings by Louis Finson, a Flemish painter and art dealer who was one of the chief exponents of the radically new Caravaggesque style and who produced numerous copies of the master’s originals.

The Brera will also be hosting the first public display of Judith Beheading Holofernes from a private collection. Several scholars have argued that this picture, which was found in 2014 in the attic of a house in Tolouse where it had been in storage since at least the middle of the 19th century, is the original that Finson copied. The mooted reconstruction suggests that this Judith was in Finson’s and Vinck’s workshop until early in 1613, when it was taken to Amsterdam along with another painting that the two artists owned, but that all trace of the picture was lost when Finson died.

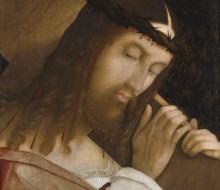

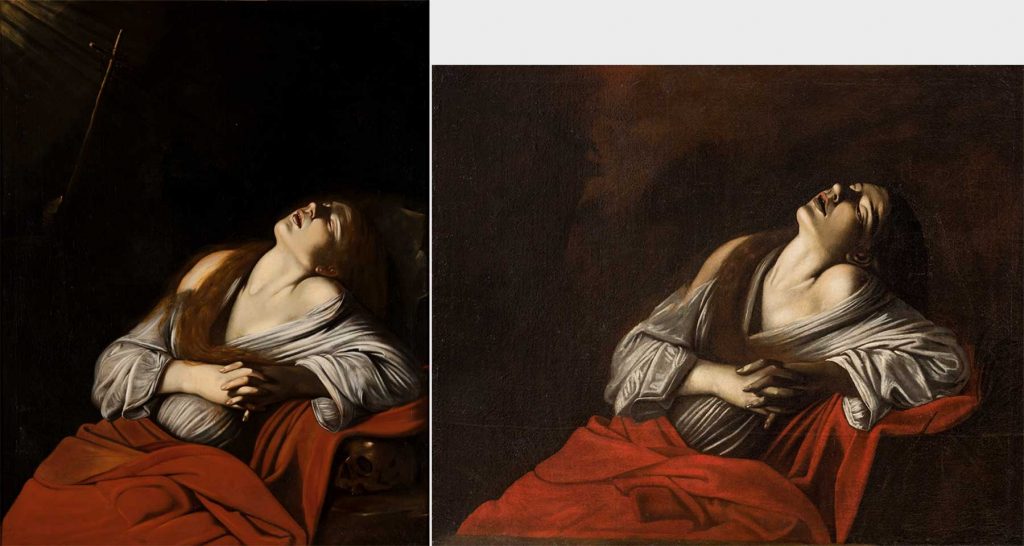

On the right, Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio*, Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1606–7, 144 x 173.5 cm (Tolouse, private collection, currently in the guardianship of the French Ministère de la Culture).

* This attribution is a condition of loan and does not necessarily reflect the official position either of the Pinacoteca di Brera or of its board of directors, advisory committee, director or staff

The loan is exceptional in every sense, not only because the painting is currently under the protection of the French Culture Ministry but also because it has been the subject of controversial study in recent months in connection with its identification as an original Caravaggio. So visitors to the Brera will have the first public opportunity ever to inspect it “from life”, so to speak, and to verify for themselves both its similarities and its differences compared to Caravaggio’s known style. And that is not all. They will also be able to draw parallels with another Judith from the Gallerie d’Italia collection housed in Palazzo Zevallos in Naples, know to be a copy of Caravaggio’s original and currently attributed to Louis Finson.

To mark the occasion, a day-long seminar behind closed doors will be convened before the end of January 2017, with the world’s leading Caravaggio experts being invited to debate the issue and with the ensuing publication of the proceedings.

On the right, Caravaggio (copy after) Magdalen in Ecstasy, after 1610, oil on canvas, 100 x 123.5 cm (Paolo Volponi collection)

Another extremely interesting part of the Dialogue will be devoted to the interaction between Finson’s Magdalen in Ecstasy from the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Marseille and a painting of exactly the same subject from the Paolo Volponi collection, one of the eight paintings by different artists reputedly copied from Caravaggio’s original. In this emblematic case too, a comparison may be made with the Brera’s own Caravaggio masterpiece, the Supper at Emmaus.

Caravaggio’s original Magdalen in Ecstasy, which has not yet been found, is thought to have been painted at the same time as the Brera Supper, in other words while the painter was sheltering on the Colonna estates after fleeing Rome following the crime that he had committed on 28 May 1606.

And the story will come full circle with a third painting by Finson, a Samson and Delilah, also from the museum in Marseille, that is considered to be one of this Flemish painter’s best works. Attribution is a topic that has also been a source of inspiration for writers, and indeed Alan Bennett wrote in his 1989 play entitled “A Question of Attribution”*

“The paintings of that period are seldom false, Your Majesty. Sometimes they are other than what we think they are, but that’s a different matter. That’s not how we should address the issue. We mustn’t ask ourselves: ‘Is this a fake?’ but rather: ‘Who painted this picture and why?”

Given that attribution plays a crucial role in art history, the best way to verify an attribution is to place the paintings side by side in a dialogue offering both art historians and the general public a unique opportunity to do just that,” says James Bradburne, director of the Pinacoteca di Brera and Biblioteca Braidense, adding: “A museum does not take any responsibility for attributions supplied by lenders, be they from the public or the private sector. Thus if the Toulouse Judith is attributed by its owner to Caravaggio, the copy is attributed to Louis Finson. So we’re hanging a signed Finson alongside a copy of the lost original. The journey from speculation to certainty is filled with debates among the experts a long time before a work of art ever enters a museum; and even then, further research can change an attribution at any time”. In other words, English playwright Alan Bennett could have been talking about Caravaggio when he wrote:

“This painting is an enigma, and such enigmas as this for an art historian can turn into research lasting years […] And even though the solution to an enigma often allows us to appreciate a painting better, we should never forget that paintings aren’t there just to be resolved. A masterpiece will always escape us: art will always escape our interpretation”.

Religious Themes

In addition to reflecting on the question of attribution, the third Dialogue, Caravaggio: “A question of attribution”, also allows us to review the artist’s handling of religious themes, for which he frequently looked to the Counter-Reformation. In particular, his numerous versions of the story of Judith and Holofernes, which tells of that Assyrian general’s beheading, is from the Book of Judith, a book that the Jewish Bible does not include and that the Protestants consider to be apocryphal. The Supper at Emmaus is also very explicitly a work of the Counter-Reformation, the figure of Christ being associated with the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation recently reaffirmed by the Council of Trent, in which the communion host becomes the Body of Christ if consecrated by a priest or, as in the painting, by Christ himself who is shown blessing the bread.

Caravaggio and his “Friends”

This dialogue is a very special event for the Brera, not only because it marks the 90th birthday of both the Friends of Brera and of its Chairman, Aldo Bassetti, but also because the association, which has always been a driving force behind the Pinacoteca’s development, feels an especially strong bond with Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus. The artist himself sold the painting to the Marchesi Patrizi, who owned it without a break until it was bought for the Pinacoteca from Patrizio Patrizi in 1939 using funds raised by the Friends of Brera.

The Vision of the “Living Museum”

Caravaggio: “A question of attribution” brings to a close a year that has seen a fully-fledged Copernican revolution for the Pinacoteca, which continues with this Dialogue to develop the vision of a “living museum” first launched by Soprintendente Franco Russoli in the 1970s. The Dialogue will tie in with the renovation of seven rooms in the Pinacoteca (bringing the total number of rooms renovated in 2016 to twenty) as part of a project in stages that will eventually involve the entire museum circuit over a period of three years. On this occasion the rooms that have been renovated lie along the Pinacoteca’s southern wing and house a rich selection of paintings stretching from the Mannerist to the Baroque eras and comprising rooms 27 (Mannerists), 28 (From Naturalism to Classicism, From Annibale Carracci to Caravaggio), 29 (Naturalism: Painting in Rome and Naples After Caravaggio), 30 (the 17th Century Lombard School), 31 (Rubens: From the Picturesque to the Baroque), 32 (Portraits) and 33 (Nature Posing).

The paintings will be enhanced by totally new explanatory texts and a new led-based lighting system sponsored by the Friends of Brera, while the walls have been repainted in accordance with a colour scheme ranging from moss green to chocolate to reflect the various historical periods, and new and more structured captions have been penned by such writers as Tiziano Scarpa (who wrote the caption for the Supper at Emmaus), Lisa Hilton and Tim Parks.

In the words of James Bradburne, “museum installations have to change in order to continually ‘replay’ the collection, in the same way as Verdi is replayed at the Scala every year. A museum that no longer believes in its collection has lost its way, of course, but the collection alone is not sufficient. The visitor must be prepared to experience it, and so we need to create a strong emotional charge around the work of art.

This happens when visitors actively use their minds to penetrate inside the work, to examine its details, to explore its images in order to be moved by the artist’s technique or by the work’s meaning, and to share their emotions with others.

If visitors are distracted by poor lighting, disturbed by rude staff or irritated by illegible and incomprehensible captions, then they are unlikely to be in the receptive frame of mind required to penetrate with their imagination inside a work of art and to take away with them even only a part of what the artist has put into it. It is this ability to visualise each potential visitor’s needs and to prepare him or her to accept the sometimes difficult pleasure of forging a one-to-one rapport with art that makes the difference between what is merely a great collection and what is a truly great museum”.

Study day at Brera

Monday, a day after the closing of the third dialogue at Brera with the exhibition of the newly discovered and much discussed painting of Judith and Holofernes attributed to Caravaggio, a group of invited specialists and conservators assembled for a morning of talks and an afternoon of discussion before the picture and the copy of it that belongs to the Banca Intesa di San Paolo, Naples.

As James Bradburne emphasized in his introductory remarks, if a museum is not a place “per facilitare lo studio e la conoscenza” – a place where one can “aprire e facilitare il discorso”, then it has not served its public or fulfilled its obligation to deepen our knowledge of the works of the great masters.

What follows is not so much a summary as a digest of the major points of the day.